A multi-institutional study on dengue led by researchers at IISc shows how the virus causing the disease has evolved dramatically over the last few decades in the Indian subcontinent.

Cases of dengue – a mosquito-borne viral disease – have steadily increased in the last 50 years, predominantly in the South East Asian counties. And yet, there are no approved vaccines against dengue in India, although some vaccines have been developed in other countries.

“We were trying to understand how different the Indian variants are, and we found that they are very different from the original strains used to develop the vaccines,” says Rahul Roy, Associate Professor at the Department of Chemical Engineering (CE), IISc, and corresponding author of the study published in PLoS Pathogens. He and collaborators examined all available (408) genetic sequences of Indian dengue strains from infected patients collected between the years 1956 and 2018 by others as well as the team themselves.

There are four broad categories – serotypes – of the dengue virus (Dengue 1, 2, 3 and 4). Using computational analysis, the team examined how much each of these serotypes deviated from their ancestral sequence, from each other, and from other global sequences. “We found that the sequences are changing in a very complex fashion,” says Roy.

Until 2012, the dominant strains in India were Dengue 1 and 3. But in recent years, Dengue 2 has become more dominant across the country, while Dengue 4 – once considered the least infectious – is making a niche for itself in South India, the researchers found. The team sought to investigate what factors decide which strain is the dominant one at any given time. One possible factor could be Antibody Dependent Enhancement (ADE), says Suraj Jagtap, PhD student at CE and first author of the study.

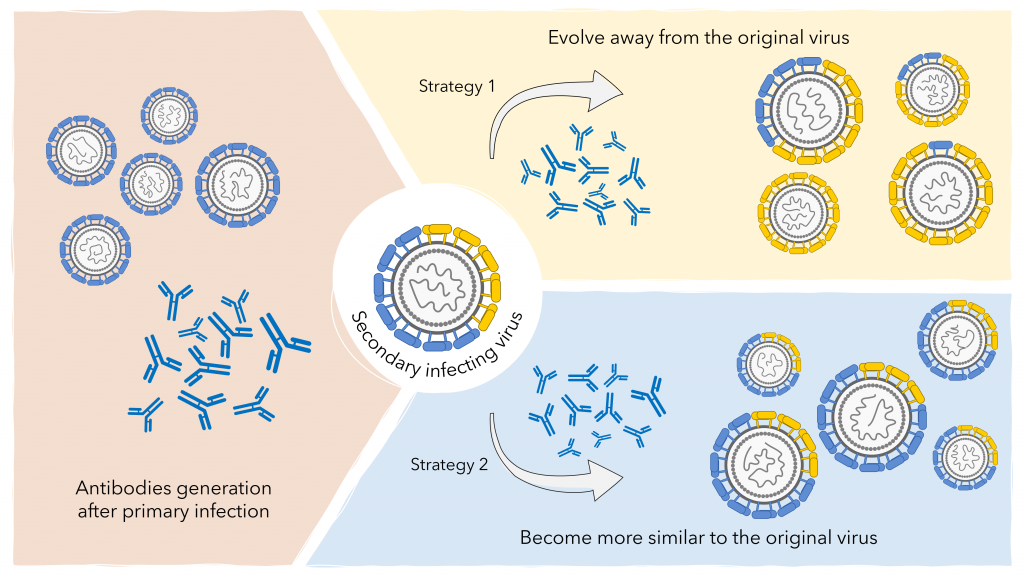

Jagtap explains that sometimes, people might be infected first with one serotype and then develop a secondary infection with a different serotype, leading to more severe symptoms. Scientists believe that if the second serotype is similar to the first, the antibodies in the host’s blood generated after the first infection bind to the new serotype and also bind to immune cells called macrophages. This proximity allows the newcomer to infect macrophages, making the infection more severe. “We knew that ADE enhances severity, [but] we wanted to know if that can also change the evolution of dengue virus,” Jagtap adds.

At any given time, several strains of each serotype exist in the viral population. The antibodies generated in the human body after a primary infection provide complete protection from all serotypes for about two to three years. Over time, the antibody levels begin to drop, and cross-serotype protection is lost. The researchers propose that if the body is infected around this time by a similar – not identical – viral strain, then ADE kicks in, giving a huge advantage to this new strain, causing it to become the dominant strain in the population. Such an advantage lasts for a few more years, after which the antibody levels become too low to make a difference. “This is what is new about this paper,” says Roy. “Nobody has shown such interdependence between the dengue virus and the immunity of the human population before.” This is probably why the recent Dengue 4 strains, which supplanted the Dengue 1 and 3 strains, were more similar to the latter than their own ancestral Dengue 4 strains, the researchers believe.

Such insights are possible only from studying the disease in countries like India with genomic surveillance, explains Roy, because the infection rates here have been historically high, and a huge population carries antibodies from a previous infection.