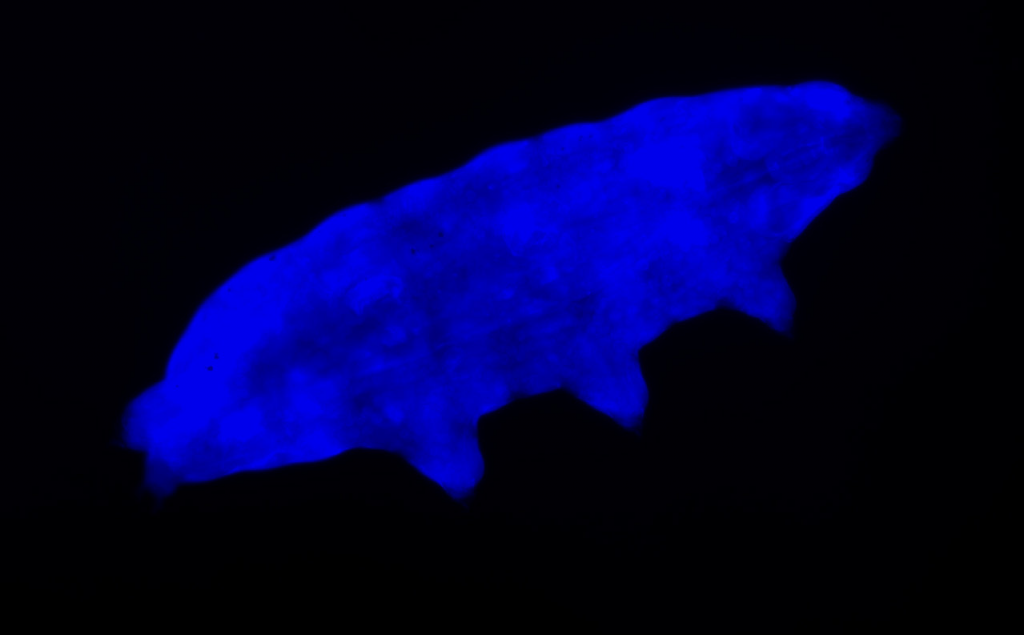

These tiny creatures can survive ultraviolet radiation by glowing blue, a feat that adds to their reputation as an indestructible micro-animal

(Photo: Harikumar R Suma and Sandeep M Eswarappa)

Tardigrades are tiny, millimeter-sized creatures that have fascinated the scientific community for a while now – understandably so – as not many animals can claim the ability to survive five mass extinctions. Due to their appearance, tardigrades are endearingly called moss piglets or water bears.

Sandeep Eswarappa, Assistant Professor in the Department of Biochemistry, has been studying these water bears for the past five years. “I watched this popular science-based TV series called Cosmos presented by Carl Sagan and later by Neil deGrasse Tyson. One of the episodes that stuck talked about the microcosmos present in a single drop of water. It mentioned tardigrades and how they have survived five mass extinctions. This episode got me interested in them,” he explains. Incidentally, his postdoc mentor had trained under Carl Sagan. As a biochemist, the nudge to study less explored model systems – E. coli, yeast and mice are already well explored – also pushed him closer towards tardigrades.

Although tardigrades were first discovered by German zoologist Johann August Ephraim Goeze in 1773 – he gave them the name water bears – research on them is even now in its nascent stage.

What makes these creatures unique is the fact that they can tolerate harsh conditions such as extreme temperature and pressure, ionising radiations, osmotic stress, and even the vacuum of space. By studying tardigrades, researchers hope to learn the mechanisms by which they can tolerate extreme physical stresses, and hopefully apply these findings to help humans cope with similar conditions.

Eswarappa points out that understanding tardigrades’ stress tolerance has significantly improved in the last five years and this could potentially lead to useful applications.

In a recent study, for example, his lab discovered a new species of tardigrades (Paramacrobiotus sp.) that can tolerate harmful UV radiation. When exposed to lethal UV radiation, these tardigrades withstood the rays by absorbing them and releasing a fluorescent glow. “They use a fluorescent shield that absorbs harmful UV radiation and emits harmless blue light as fluorescence. Interestingly, we could transfer this UV tolerance property to another tardigrade, Hypsibius exemplaris, which is otherwise sensitive to UV radiation,” says Eswarappa.

Their study offers direct evidence that fluorescence in organisms provides photoprotection, he points out. “Photoprotection against UV radiation has been suggested as a possible function of fluorescence in some organisms such as amphioxus, comb jellies and corals. However, there was no direct experimental proof of this in any organism, until our study,” he says. His team is now focusing on identifying the chemical nature of the fluorescent compound.

Such insights could even come in handy in our day-to-day lives. “This research can potentially lead us to develop a novel UV-protective (sunscreen) compound,” he points out. The same compound could also be used to make UV-protective windows and screens.

Eswarappa’s lab is also collaborating with physicists and chemists to learn more about these fascinating creatures. “We plan to investigate their ability to tolerate complete desiccation and thermotolerance. We are also interested in studying their metabolism and translation [one of the steps in protein synthesis] during their hibernation state, called ‘tun’ state.”

There are still many mysteries yet to be solved when it comes to tardigrades. A recent study, for example, showed that some tardigrades cannot survive extreme heat, unusual for an animal pegged to survive almost anything. But that may not be as surprising because there are over 1,000 known species of tardigrades, says Eswarappa. “Not all of them will show thermotolerance. They have evolved tolerance according to their environment.”