In India, rivers are not just lifelines, they are also primal forces. Notwithstanding high rainfall, tropical cyclones, and climate change, the country’s geography is a trap for water overflows. According to the National Remote Sensing Centre, ISRO, India is the second-most flood prone country in the world. About half of casualties due to natural disasters are purely due to flooding. But what if we could predict when or where it could happen? Researchers at IISc are currently on a mission to revitalise the mapping of India’s river floods. Using statistical modelling, they are studying whether Peninsular Indian rivers are similar to each other in terms of their flood behaviour.

“Flood risk assessment studies should not be restricted to individual basins,” says Shailza Sharma, Researcher at ICAR-CRIDA and former postdoc at the Department of Civil Engineering, IISc. “Due to climate change, spatial dependencies of different rivers flooding concurrently should be investigated.”

As a result of climate change, rains in India have become shorter in duration and greater in intensity. This can lead to high surface runoff – water that collects and flows on top of the ground instead of seeping into the soil – and increased likelihood of synchronised floods across multiple river basins. The Central Water Commission (CWC) oversees the current flood data that is used to map and predict floods, but the risk is often measured at individual river basins. According to Shailza, the lack of observed streamflow hindered advancements on understanding and predicting river floods in India.

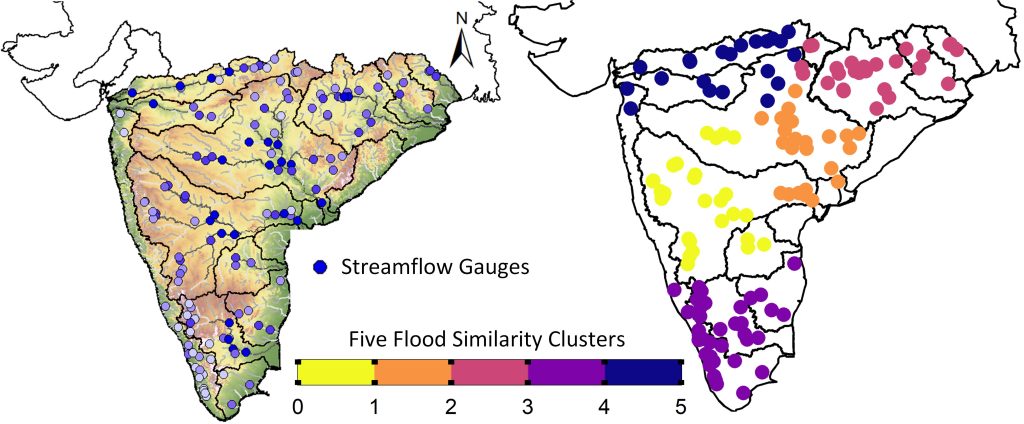

Instead of mapping flood risk at individual locations, Shailza and others focused on regional trends and spatial similarities to better understand flood co-occurrence. In a recent study published in Scientific Reports, they assessed data from 137 streamgauge stations and mapped water levels. They then analysed how the increase in water levels was influenced by time and geography and identified five groups of rivers displaying similar flood behaviour.

Surprisingly, they found that floods seem to be connected beyond individual river basin boundaries in Peninsular India. Even geographically unconnected rivers showed flood cooccurrence, which may be influenced by similar meteorological processes and surface conditions. In most catchments, flood connectedness appears to have increased in recent years compared to the past.

Previously, the team, which includes faculty member Pradeep P Mujumdar, worked with researchers at IIT Roorkee to create a dataset called CAMELS-IND. This dataset captured characteristics of catchments across the country, such as water flow, water levels, humidity, temperature, wind, soil characteristics, dams, and human activity among others, observed between the years 1980 and 2020.

“Inconsistent data is hindering work in Indian catchment hydrology,” says Kanneganti Bhargav Kumar, PhD student at IISc and the first author of the study. This inconsistency can take many forms like missing data values, or an uncertainty in the true value due to unexpected changes in flow. This can make it harder to understand and predict floods. He also points out that although India is highly vulnerable to concurrent flood events, the underlying factors have not been studied in detail. This new research, therefore, fills a critical knowledge gap.

Reservoirs – whose operations are governed by human decisions – also play a significant role in influencing river flow and flood behaviour, complicating statistical modelling efforts. “Peninsular India is heavily regulated by reservoir operations, which are difficult to incorporate into models,” adds Shailza. “That’s a major limitation to overcome.”

While well-managed reservoirs can reduce the severity and volume of floods, poor design, operation, or maintenance can exacerbate risks. Integrating reservoir operations into hydrological models, alongside reliable flood and rainfall forecasts, could greatly improve flood preparedness, risk assessment, and planning efforts.

In the future, the researchers hope to develop improved statistical models for better flood forecasting. “India is just beginning catchment hydrology studies with the release of the CAMELS-IND data,” expresses Bhargav. “We’re taking baby steps now … once we understand the underlying hydrological processes, then we can move toward more effective mitigation strategies.”