Soils are reliable sinks for trapping carbon, which is key to mitigating the effects of climate change. Grazing by large mammals favours soil carbon storage in grasslands, but around the world, wild herbivores are gradually being replaced by livestock. In the Spiti region of the Himalaya, researchers at the Centre for Ecological Sciences (CES), IISc, have found that grazing by livestock leads to lower carbon storage in soil compared to grazing by wild herbivores.

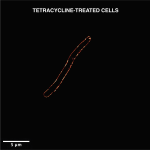

Part of this difference appears to be due to the use of veterinary antibiotics such as tetracycline on livestock. When released into the soil through dung and urine, these antibiotics alter the microbial communities in soil in ways that are detrimental for sequestering carbon. In such areas, “rewilding” the soils – restoring beneficial microbes lost due to antibiotics – could help offset the damage, the researchers say. Quarantining animals that are given antibiotics until the medicines pass out of their system could also help reduce their impact on soil.

“Today, livestock are the most abundant large mammals on Earth,” says Sumanta Bagchi, Associate Professor at CES and corresponding author of the study published in Global Change Biology. “If the carbon stored in soil under livestock can be increased by even a small amount, then it can have a big impact on climate mitigation.”

In a previous study, the researchers had shown how grazing by herbivores plays a crucial role in stabilising the pool of soil carbon in the same region. In the current study, they set out to ask the question: Are livestock such as sheep and cattle similar or different in how they affect the soil carbon stocks compared to their wild relatives such as the yak and ibex?

To answer this, the researchers studied soils over 16 years in areas grazed by wild herbivores and by livestock respectively, and analysed them for various parameters including microbial composition, soil enzymes, carbon stocks, and the amount of veterinary antibiotics. “This is part of a long-term study on ecosystem functions and climate change in the Himalaya, which was started in 2005,” explains Bagchi.

Although soils from the wild and livestock areas had many similarities, they differed in one key parameter called carbon use efficiency (CUE), which determines the ability of microbes to store carbon in the soil. The soil in the livestock areas had 19% lower CUE.

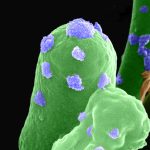

When they probed further for potential explanations, the researchers found that the soil microbial composition in areas with livestock was different from the areas with wild herbivores. Finally, they also found higher levels of antibiotic residues in soil under livestock. “This highlights how human land use, antibiotics, microbes, soils, and climate change are deeply connected,” says Dilip Naidu, PhD student at the Divecha Centre for Climate Change, IISc, and an author of the study.

“What is interesting,” Bagchi adds, “is that antibiotic usage in pastoral ecosystems like Spiti is fairly low.” The situation could be worse in areas where livestock are reared at large scales, and where they are often given antibiotics even when they are not sick, he points out. Antibiotics such as tetracycline are long-lived and can linger in the soil for decades. “Their unregulated use not only threatens climate but also poses the risk of evolution of antibiotic resistance in pathogens that can cause difficult-to-treat infections in humans and animals,” says Shamik Roy, former PhD student at IISc and lead author of this study.

“We do not yet fully understand the details of the underlying mechanisms of how soil microbial communities respond to the antibiotics, and whether they can be restored easily,” adds Roy. In future studies, the researchers plan to investigate how better management of livestock can mitigate their negative impacts on the environment, alongside microbial restoration.