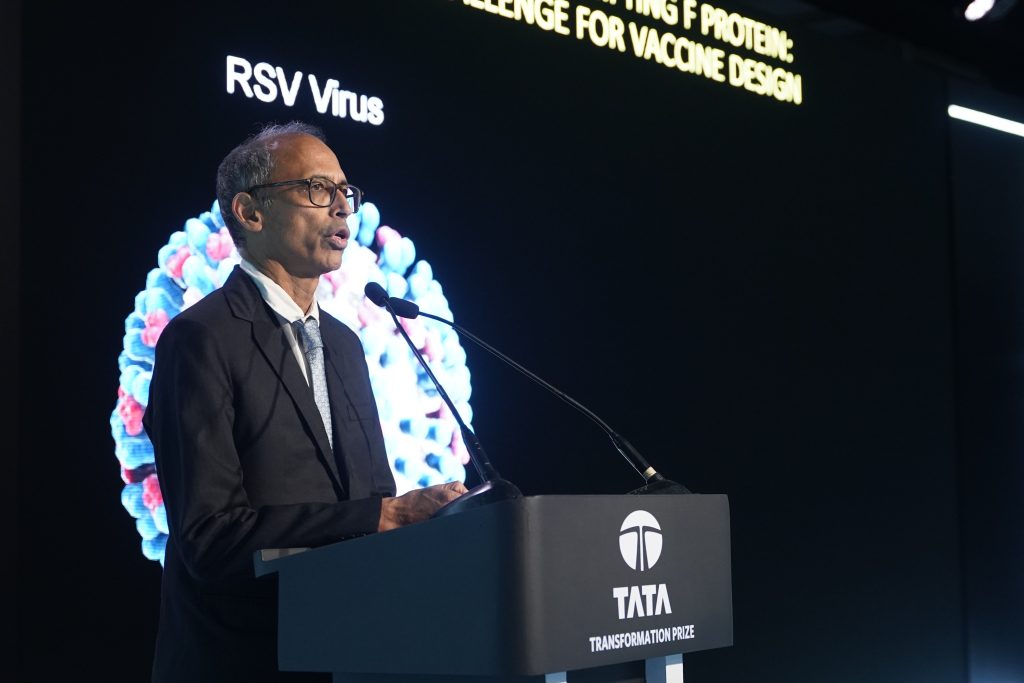

Raghavan Varadarajan, Professor at the Molecular Biophysics Unit (MBU), recently won the Tata Transformation Prize for proposed work on developing a vaccine for Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV). In this short interview, he outlines the goals and potential impact of the project.

Your proposal seeks to develop a vaccine for Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV). Could you tell us more about this research and what inspired you to focus on it?

RSV is a respiratory virus, and it is an important vaccine target because it kills a lot of children, especially in developing countries. We have previously worked on some important respiratory viruses such as influenza and COVID-19. Using our expertise in designing vaccines, we want to create an affordable vaccine for RSV, given that current vaccines are very expensive.

You talked about RSV being a big challenge for developing countries. How significant is this challenge in India?

In low and middle-income countries, the total death toll is over 100,000 a year. Given the size of India’s population, a reasonable fraction of the population is likely getting infected. There is no official statistic for India, but if one just compares the proportion, I would estimate the number to be around 20,000. However, this is not a rigorous estimate. The overall disease burden is known, and India is likely to have a significant fraction of it.

What impact do you think the development of this vaccine could have?

The death toll is quite high annually, and the vaccine is not available to most of the people who need it. If we can reach even a fraction of people who really need it in developing countries, and if we can show that it is safe for pregnant women, that would have the maximum impact.

However, developing vaccines for children will take some time because they can only be developed after all other age groups are tested and the vaccine is proven to be safe and efficacious. In addition to alleviating human suffering, there is also economic benefit; every time a child falls sick, it also means a lot of work for parents, along with the added cost of hospitalisation.

Why are current vaccines so expensive, and how do you plan to develop a low-cost vaccine?

The list price is about $300 for a single dose. The reason it is so high is that a significant amount of time and money goes into the development of these vaccines, and, of course, the companies need to make a reasonable profit.

In our case, I believe our developmental cost will be much lower, and we are also not aiming to make a large profit from this. Additionally, because of previous work, both ours and others’, we know how to approach the problem and what is required to make a good vaccine. This will accelerate our work quite a bit.

The work is at a relatively early stage. We have done some preliminary experiments and have some promising results. However, once we start getting funds, we will be able to move much faster on this.

Can you share with us a bit about the broad areas that your lab works on?

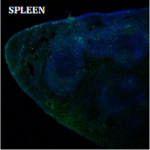

We work on proteins in general and how to stabilise them so that they don’t aggregate or unfold. This is important for developing vaccines.

We have developed vaccines for different pathogens, including influenza, SARS-CoV-2 which caused COVID-19, and other similar viruses; we have also worked on HIV-1 for which no vaccine currently exists. We have been working in this area for many years, and RSV became the next important target we wanted to tackle. RSV is similar to HMPV (Human Metapneumovirus), which has caused a recent outbreak in China.

What does this prize mean to you as a scientist?

It is good to be recognised, and most importantly, it gives us money to do the work that we proposed. In addition, having recognition from the Tata group would eventually aid in clinical development and commercialisation, as they can connect us with people who can help with these later steps.

What advice would you give to innovators in the healthcare field?

It is very difficult to answer because it depends on the challenges one faces, and on where the person is working – whether in academia, startups or larger companies. However, I would suggest picking an important problem early in one’s career and then finding the right environment and funds to take the work forward.