The cornea – the transparent, outermost layer of our eyes – is soft and squishy, yet one of the toughest known materials. It is a type of hydrogel – a material made of cross-linked chains of repeating molecules called polymers, which can hold over 78% water. Engineered hydrogels, like polyacrylamide gels used in molecular biology labs, are nowhere near as tough.

“The cornea is the best kind of natural hydrogel,” says Namrata Gundiah, Professor at the Department of Mechanical Engineering at IISc.

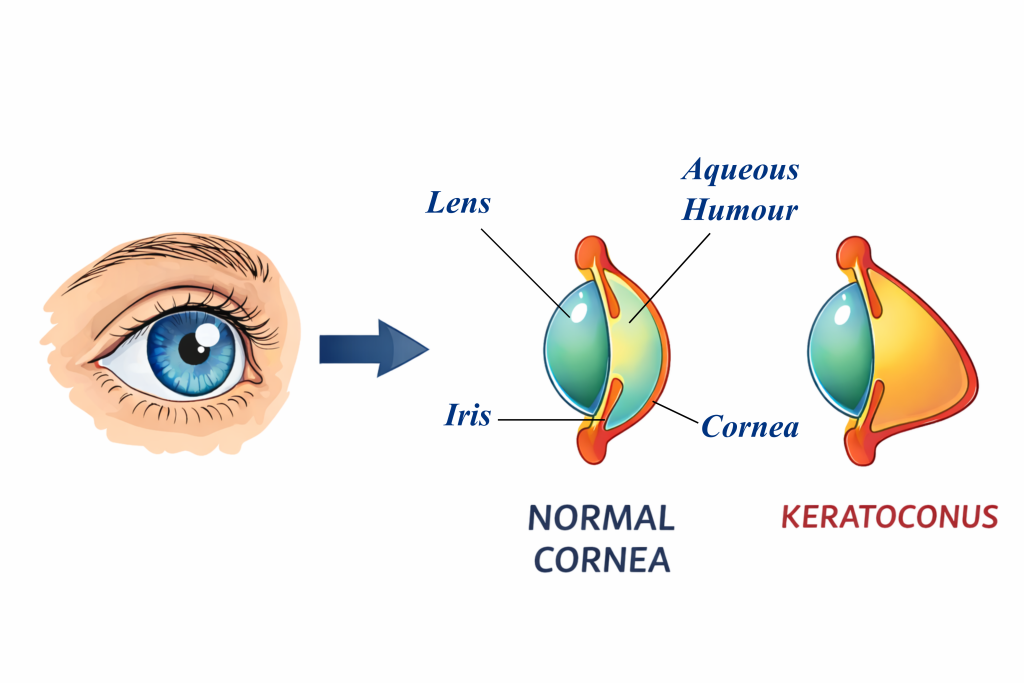

Made up of inter-connected fibres of a natural polymer called collagen along with a few cells, the cornea is crucial for controlling how light enters our eyes. However, despite its strength and durability, it can sometimes get progressively damaged. In a condition called keratoconus, loss of collagen fibres and a reduction in their cross-linking causes the cornea to thin out non-uniformly. This makes it less resistant to mechanical forces like intra-ocular pressure (pressure from the fluid in our eyeballs).

Think of a water balloon that happens to be thin, and thus bulging, at some spots. Something similar happens in keratoconus eyes as well, explains Anshul Shrivastava, a former graduate student in Namrata’s group. “The cornea in our eyes is naturally curved. But there is an abnormal change in its curvature in keratoconus patients,” he says. This increased curvature can result in major vision problems, from irregular astigmatism to loss of sight.

To address this challenge, Namrata and her group, in collaboration with Narayana Nethralaya, used the goat cornea as a model system to dive deep into its nature and properties. In a recent study, they looked at how a decrease in collagen content affects the microstructure of its fibres, and how that, in turn, influences the cornea’s mechanical properties. They found that even a short-duration treatment with collagenase – an enzyme that breaks down the collagen network – dramatically decreases corneal stiffness.

In contrast, treating collagen fibres with a cross-linking chemical called methylglyoxal (MGO) made the corneal tissue much stiffer. This builds on previous work in the lab, where Anshul and Namrata showed that treating synthetic hydrogels made of gelatin with MGO creates more cross-linking and makes the gel tougher.

To simulate the progressive thinning of the cornea in keratoconus, the researchers treated the goat cornea with collagenase for increasing periods of time – 15, 30, and 60 minutes. Surprisingly, the cornea became highly stretchable after just 15 minutes of treatment. But the collagen content had reduced only by about 5%.

When they looked closer at the collagen’s microstructure, they found that with an increase in the treatment time, the usually straight collagen fibres become more curved – their “tortuousity” increases. Curved fibres find it harder to bear mechanical loads, and buckle and stretch more easily.

“You can think of a thread which is properly taut; if we pull it, it can directly [offer] some opposing force. But if it is curved then it cannot,” explains Anshul.

These microstructural changes could be driving keratoconus as well. “If you have all these crumpled up or wrinkled up collagen, the way the light is being let inside is going to get altered,” says Namrata.

Usually, doctors use a molecule called riboflavin to UV-cross-link the collagen in keratoconus patients, but this method can damage the retina if the cornea is already too thin. The researchers instead adopted a novel route: using MGO to increase the number of covalent bonds between the collagen fibres, in a method called non-enzymatic cross linking. As the collagen became more cross-linked, the cornea’s stiffness increased, showing that this technique could potentially treat a weakening keratoconus cornea.

The researchers were also able to link the cornea’s elastic modulus – a measure of its stiffness – with the amount of collagen using a scaling model. This can potentially be used for diagnostics in the future, Anshul says. The team now plans to study this further in human cornea slivers called lenticules.

Namrata believes that the observed microstructural changes in collagen fibres also have implications for mechanobiology – the study of how mechanical changes in the cell influence the proteins it makes. Under normal conditions, the straight collagen fibres hold the cells under tension, but in diseased conditions, this tension is affected. “The minute you snip that tension and you put them in a different mechanical state, it could produce different kinds of proteins that can exacerbate the condition,” she explains. “That’s what we’d like to investigate next.”