Bringing board games into the realm of research

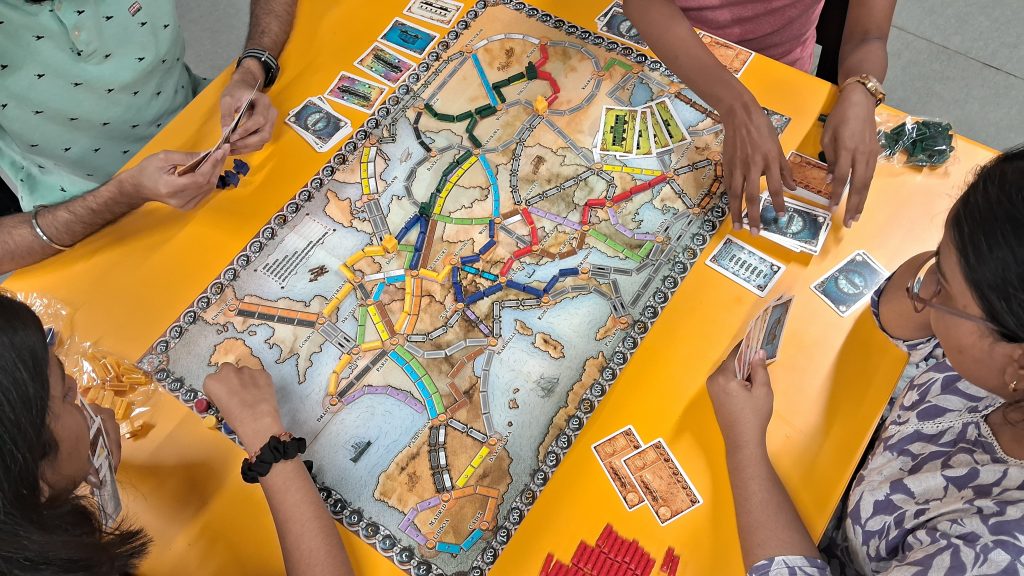

Long before we learned to split the atom or sequence a genome, we learned to play. Games have long been used as tools for social bonding and storytelling. In recent years, there has been growing interest in using structured play to reveal deeper patterns of human behaviour and decision-making. Scientists and policymakers alike are asking: Can games be used to explore human complexity?

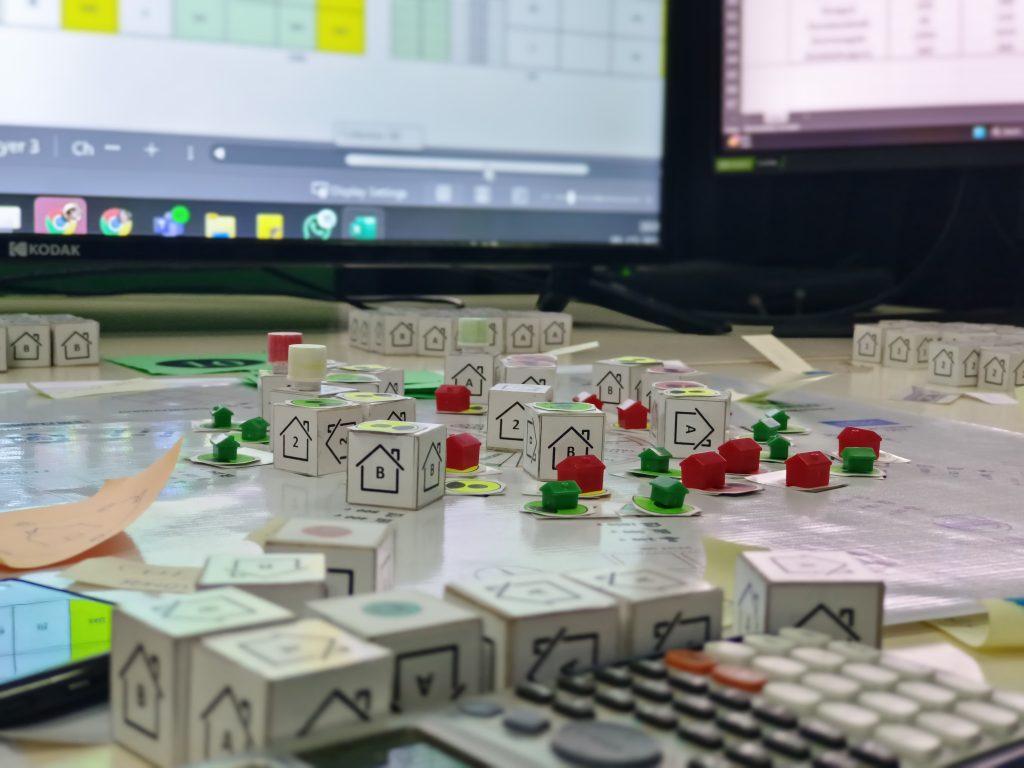

This is the same question that Vighneshkumar Rana, a research scholar at the Department of Design and Manufacturing (DM), IISc, has been contending with. He realised that people’s decision to purchase a house is skewed towards location, relatively undermining the quality of the house. This led him, he says, to wonder whether decoupling the housing unit from the location could transform the real estate industry and enhance the adoption of innovation in housing solutions. To explore this, he designed a real-estate-themed board game – Real Estate Navigator – in which players take on fictional roles, find jobs, receive salaries, and invest their money in housing. There are two types of housing to choose from – houses that depend on the location in which they are situated (coupled) and houses that are modular and mobile and therefore, independent of location (decoupled).

The goal was to place participants in realistic decision-making scenarios, instead of merely conducting interviews. “People say one thing during interviews but do another when they play,” he says. For example, someone who claims they would never invest in a risky asset might do so in the game when faced with simulated market competition or peer pressure. Since board games are more immersive, the decisions that people make during gameplay often reflect their real-life behaviour more accurately.

Refined through multiple iterations, the game functions as both a design artefact and a behavioural testing ground. Vigneshkumar complements gameplay insights with agent-based simulations, to use the patterns observed in the game to calibrate computational models that can test different housing scenarios across large virtual populations. “The idea is to run ‘what-if’ experiments,” he says. “We might test how introducing a modular housing option affects investment behaviour, affordability, or market saturation in the long run.”

Vigneshkumar’s advisor, Vishal Singh, who is an Associate Professor at DM, feels that games should not be seen only as a linear cause-and-effect chain but as a small, controllable version of a complex web of social, economic, and psychological factors. “You can’t run a city-level housing trial in the real world,” he explains. “But you can create a simulated environment where people operate with bounded knowledge and social influence, allowing their decisions to reveal heuristics rather than formal optimisation.”

He points out that decades of design and behavioural research point to the same truth: When the world gets too complicated, people simplify. Drawing on the influential scientist Herbert Simon’s idea of “satisficing” – the notion that most of the time people, don’t obsess over perfect solutions but use simple rules of thumb to reach good-enough solutions – he explains that observing how players resort to shortcuts inside a game helps researchers trace hidden logic behind real-world decisions. These can then be woven back into more nuanced research models that can help simulate ideas on a scale that board games alone cannot.

Learning through games

Besides using games to gather insights, researchers are also using them as a fun and relatable tool to impart knowledge. For example, Kavyashree Venkatesh, a PhD student at IIT Guwahati, developed a board game called Bio-Bridge that introduces teenagers to the concept of biomimicry. In her game, each player flips over a hidden tile and tries to link the product it shows to one of their animal cards, drawing a connection to how nature might solve a similar problem. If they find a match, they claim the tile and score a point. As the game goes on, players strategically line up cards for valuable bonus points. Small moves like nudging a card just one step can simply outwit their opponents and make the game fun and engaging.

Finding the right balance between making sure the game is fun and retaining its scientific depth intact was no easy feat, Kavya admits. But playtesting offered some surprising insights. “Children started exploring parts of the game beyond what we had originally designed for,” she says. “They not only say whether they like it or not, but also suggest possible improvements.”

Kavya sees this openness – players’ freedom to interpret – as the core of the educational value of games. “You’re not just delivering information,” she explains. “You’re creating a fun structure within which their intuition can guide them to explore further.”

Kuksh Jain, a designer from Srishti Manipal Institute of Art, Design and Technology, takes the idea of complex systems to the ground, literally. In his board game, Ant Dominion, players turn into ants trapped in a world that keeps trying to bring them down.

The game features four different ant species, such as the Indian weaver ant or black crazy ant, each with unique traits that shape how players plan and adapt. Stressed environments such as forest fires, pesticides, and pollution challenge their adaptation strategies. The goal of the game is to have the biggest colony strength.

Players collect adaptations – like resistance to pesticides, enhanced foraging abilities, or faster colony growth – but if they gather too many, their ants stop behaving like typical ants. “One player said their ant felt like a superhero,” Jain recalls. “That was the point [of the game]. At what stage does adaptation change identity?”

Rooted in interviews with biologists and field data, the game embeds real ant behaviour in its mechanics. The game was tested with children, designers, and educators. Some players asked for more randomness in the gameplay and more numbers of species. Others remarked how invested they became in the game. Kuksh remembers how the competitive spirit unfolded: alliances formed, betrayals happened, emotions ran high.

For Kuksh, the game is as much about ethics as it is about biology. “The best learning,” he says, “is when you don’t know you’re learning. You’re strategising. You’re immersed. But later, you realise: it was about survival and impact.”

A fine balance

While games may provide a fun strategy for exploring and sharing science, researchers caution against romanticising the method. “Games aren’t a shortcut,” says Muniba, a PhD student at IIT Bombay. “If anything, they require more iteration and more testing.”

Muniba is studying game creation – how student designers make choices when developing games, especially under strict constraints such as time, materials, or educational themes. Her earlier experience designing inclusive, tactile games for visually impaired children shaped her approach. “A designer should always start by spending time with the user, playing with them and watching closely how they interact,” she says. “Don’t just skim a post‑game survey – let players’ choice drive the experience to build the game.”

Kavya feels that there has to be a balance between fun and complexity. “Respect your users and your subject. Don’t oversimplify just to make it fun,” she says.

What these researchers share is the belief that play reveals what people won’t always confess in conversation. As Vishal puts it: “Games can be very engaging, which means you can get people to participate more actively than otherwise. A number of factors make games a compelling tool to support your research. It can be extremely powerful.”