Understanding how the virus fuses with host cells can point scientists to better antiviral strategies

(Image: Biswajit Gorai)

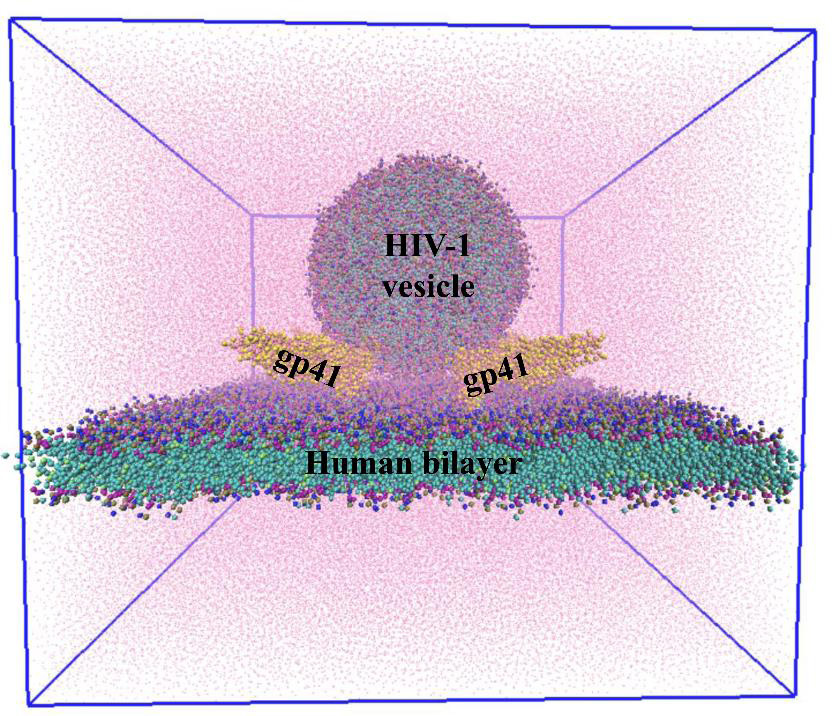

An interdisciplinary team of researchers at IISc has used robust computer simulations to understand how the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) – which causes AIDS – fuses with the host cell membrane. Published in the Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling, the study focuses on a process called gp41 mediated membrane fusion.

Gp41, a core component of the HIV envelope protein (Env), is essential for the viral membrane to fuse with the cell membrane of a type of immune cell in the host called T cell. This step is critical for HIV to invade and subsequently replicate within the host cell. “If gp41 fusion is blocked, then the whole invasion can be blocked there,” explains Biswajit Gorai, a former postdoc at IISc and first author of the study. Therefore, understanding the membrane fusion process may help researchers in developing effective antiviral strategies.

Although a lot is known about the molecular details of viral entry, the optimal stoichiometry – the balance of components – required for infection has remained uncertain. “We wanted to see … how many gp41 units are required to achieve this process,” explains Prabal K Maiti, Professor and Chair of the Department of Physics and the corresponding author.

The HIV envelope protein assembles into a three-part structure such that each unit comprises one gp41 protein. At the time of fusion, gp41 appears to fold into a six helix bundle structure, which is thought to be necessary for membrane fusion. Maiti elaborates, “There were a lot of hints from experimental work which showed that gp41 forms a six helical bundle in the post-fusion step. That prompted us to test the hypothesis that gp41 could actually help in fusion, which can eventually help virus invasion.”

The team first built computational models of HIV and host cell membranes, and then simulated the fusion process. “Initially we started with millions of atoms and it was very slow … but then we turned to a coarse-grained model, so now we can have microsecond simulations,” explains Gorai. Starting with no gp41 on the HIV membrane as the baseline, the authors incrementally added gp41 units to their simulation. On doing so, they found that at least three gp41 units act cooperatively and are necessary for fusion.

In another first, the team built models of HIV and host membranes with lipid compositions nearly identical to biological membranes. Using different membrane models, the authors showed that only the membranes with such identical lipid composition fused successfully, while the rest did not, indicating that the lipid composition of the membranes is critical for fusion.

The researchers also analysed the nature of lipid transfer during fusion and found that the trio of gp41 units drives changes to the structure and arrangement of lipids at the site of fusion. Finally, using mathematical calculations, the team found that the presence of gp41 reduces the energy required for fusion by about four-fold, thereby making this process more favourable.

Currently, the team is working on identifying mutations that can be introduced in gp41 to block the fusion step. They are also hoping to develop antibodies that can prevent infection. “Together with my colleague, Narendra M Dixit [Professor, Department of Chemical Engineering], we are trying to pursue this line of a neutralising antibody system,” says Maiti.