Scientists at JNCASR and IISc have visualised how glass transforms into a crystal for the first time in experiments

Glass is amorphous in nature – its atomic structure does not involve the repetitive arrangement seen in crystalline materials. But occasionally, it undergoes a process called devitrification, which is the transformation of a glass into a crystal – often an unwanted process in industries. The dynamics of devitrification remain poorly understood because the process can be extremely slow, spanning decades or more.

Now, a team of researchers led by Rajesh Ganapathy, Associate Professor at the Jawaharlal Nehru Centre for Advanced Scientific Research (JNCASR), in collaboration with Ajay Sood, DST Year of Science Chair and Professor at IISc, and their PhD student Divya Ganapathi (IISc) has visualised devitrification for the first time in experiments. The results of this study have been published in Nature Physics.

“The trick was to work with a glass made of colloidal particles. Since each colloidal particle can be thought of as a substitute for a single atom, but being ten thousand times bigger than the atom, its dynamics can be watched in real-time with an optical microscope,” says Divya Ganapathi. “Also, to hasten the process we tweaked the interaction between particles so that it is soft and rearrangements in the glass occurred frequently.”

In order to make a glass, the team jammed the colloids together to reach high densities. They observed different regions of the glass following two routes to crystallisation: an avalanche-mediated route involving rapid rearrangements in the structure, and a smooth growth route with rearrangements happening gradually over time.

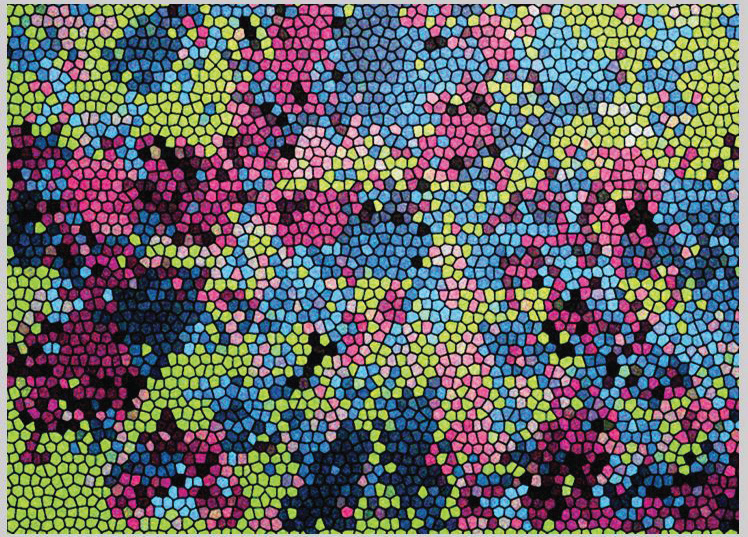

To gain insights into these findings, the researchers then used machine learning methods to determine if there was some subtle structural feature hidden in the glass that decides beforehand which regions would later crystallise and through what route. Despite the glass being disordered, the machine learning model was able to identify a structural feature called “softness” that had earlier been found to decide which particles in the glass rearrange and which do not.

The researchers then found that regions in the glass which had particle clusters with large “softness” values were the ones that crystallised and that “softness” was also sensitive to the crystallisation route. Perhaps the most striking finding emerging from the study was that the authors fed their model pictures of a colloidal glass and it accurately predicted the regions that crystallised days in advance. “This paves the way for a powerful technique to identify and tune ‘softness’ well in advance and avoid devitrification,” says Ajay Sood.

Understanding devitrification is crucial in areas like the pharmaceutical industry, which strives to produce stable amorphous drugs as they dissolve faster in the body than their crystalline counterparts. Even liquid nuclear waste is vitrified as a solid in a glass matrix in order to safely dispose of it deep underground and prevent hazardous materials from leaking into the environment.

The authors believe that this study is a significant step forward in understanding the connection between the underlying structure and stability of glass. “It is really cool that a machine learning algorithm can predict where the glass is going to crystallise and where it is going to stay glassy. This could be the initial step for designing more stable glasses like the gorilla glass on mobile phones, which is ubiquitous in modern technology,” says Rajesh Ganapathy.

The ability to manipulate structural parameters could usher in new ways to realise technologically significant long-lived glassy states.

– with inputs from the authors