Ashesh Dhawale’s lab is on a quest to decode one of the most intriguing questions in neuroscience

Switch off the alarm, pick up the newspaper, check the messages, take a bath, go on a trek, set up an experiment … Our brain seamlessly manages a range of complex coordinated tasks each day. Behind these seemingly effortless actions lie intricate neural computations. Scientists have long been fascinated by how the brain orchestrates such complex and coordinated movements. Ashesh Dhawale, a behavioural and systems neuroscientist at the Centre for Neuroscience, IISc, is tackling this problem head-on. “Using rats as a model organism, we seek to unravel how the brain learns and executes complex, real-world tasks,” explains Ashesh.

Ashesh was passionate about doing research from a very young age. He chose to pursue his BSc from St Xavier’s College in Mumbai. “My teachers here put me on a fast path towards research as a career. Fortunately, I was also one of the early recipients of the KVPY (Kishore Vaigyanik Protsahan Yojana) fellowship.” The fellowship helped him land his first internship at IISc in the lab of Usha Vijayaraghavan in the Department of Microbiology and Cell Biology, where his interactions with a then PhD student, P Sriram, shaped his understanding of research, he says.

During his undergraduate years, Ashesh was actively involved in the Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS) field studies. After completing his Bachelor’s, he went on to pursue an Integrated PhD at the National Centre for Biological Sciences (NCBS) in Bangalore. “I wanted to pursue my PhD in either ecology or developmental biology, but I changed my plans and joined a neuroscience lab,” recalls Ashesh.

His path into neuroscience was shaped by a blend of serendipity and a deep sense of curiosity. “NCBS had lab rotations for PhD students, and I was fascinated by the neuroscience course instructor, Upinder Bhalla (fondly known as Upi). I decided to change my rotations to include his lab. Upi does not dictate work to students; he rather allows them to discover their questions on their own.”

Ashesh remembers that Upi told him to build a 2-photon microscope during his rotation there, which both knew was impossible. However, the challenge convinced Ashesh to join Upi’s lab for his PhD. “I finally built the microscope two years later, and after multiple iterations,” Ashesh reminisces. “We named the microscope ‘Bheja fry (brain fry)’ after having fried a brain slice under it. The microscope has now become a part of scientific history and has been donated to the Science Gallery Bengaluru.”

His PhD thesis focused on identifying neural responses involved in odour identity, using 2-photon imaging combined with a newly developed technique called optogenetics – using light to activate neurons. In collaboration with faculty member Dinu Albeanu at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL), they mapped the neural connections involved in processing different olfactory stimuli.

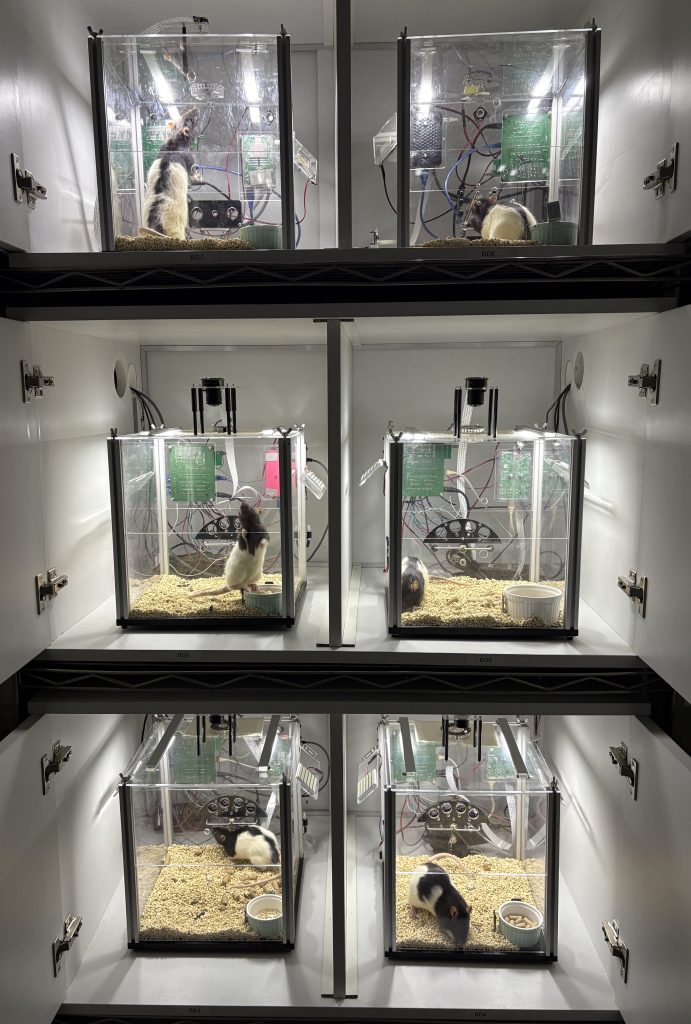

“My PhD was interesting; it involved using multiple cool techniques. But I grew more interested in understanding the fundamental principles involved in how the brain processes different kinds of information to modulate behaviour,” Ashesh explains. After his PhD, Ashesh pursued his postdoctoral studies at Harvard University under Bence Ölveczky. Ölveczky and his team had developed an automated training system for rodents. “The idea is that we build a computer-controlled training system in a rat’s home-cage. We use associative reward memory. The rats are deprived of water, and they only receive water upon successful completion of the task,” Ashesh explains.

In his postdoctoral work, he worked on developing an analysis strategy for the neural recordings obtained from this automated system. Brain recordings in live animals are performed by inserting electrodes in specific regions of the brain. In a freely moving animal, the electrode position inside the brain can change due to the soft nature of the brain tissue. “In continuous recordings, this leads to drift, and neuronal activity is disturbed,” says Ashesh. “Until then, there was no technique to sort this drift issue, and we worked on solving this, leading to us now being able to isolate the activity of individual neurons.”

“Bence is a meticulous thinker,” recalls Ashesh. His ability to manage people and his thoughtful approach to experiments influenced Ashesh’s career. “I have learnt to balance fun with rigorous science.”

Ashesh has employed his learnings to establish an independent lab at the Centre for Neuroscience in IISc. His lab has developed a similar automated training system to study how the brain learns to solve complex real-world tasks. “The neurobiology of learning has typically been studied in very simple tasks where animals choose between just two options,” he explains. “Our focus of study is to learn how we decide when there are many options, and in particular skill learning, which relies a lot on trial and error.”

“Complex movements require practice and precision. For example, take a tennis serve. If we record the trajectory of a serve from a beginner and a pro player, you will observe that the trajectory is quite similar across trials for a pro player as a result of continuous brain learning from trial and error,” he adds. Such complex motor-learning tasks are a computationally challenging problem (especially for robots), but humans and animals can do these easily. His team is investigating this learning using rats by performing neural recordings from the cortical and basal ganglia regions in the brain.

Using the rat home-training apparatus, Ashesh’s team trains rats deprived of water to perform skill learning tasks, like pushing a lever or pulling a joystick. When rats perform the correct movements, they get reward (a drop of water). Here is where it gets interesting: They challenge the rat with a different variant of the task every day. This enables the team to estimate the efficiency with which the brain adapts to such variations, another problem the lab is pursuing.

To solve these challenges, the lab uses a combination of animal behaviour, learning, neural recordings and machine learning tools. “Overall, we study the origins of brain [function] using modern tools of biology,” adds Ashesh.

When not doing science, Ashesh enjoys nature walks, bird watching, trekking, and travelling. He loves to tune into classical music and immerse himself in it amidst his chaotic work schedule. For aspiring researchers, Ashesh has the following advice: “Academia comes with a lot of task juggling, but at the end of the day, passion towards doing and enjoying science makes it worthwhile.”