Researchers at the Solid State and Structural Chemistry Unit (SSCU) and their collaborators have discovered how next-generation solid-state batteries fail, and devised a novel strategy to make these batteries last longer and charge faster.

Lithium-ion batteries – the kind that you might find in your smartphone or laptop – contain a liquid electrolyte sandwiched between a positively charged electrode (cathode) and a negatively charged electrode (anode), usually made of graphite. When the battery is charging and discharging, lithium ions shuttle between the anode and cathode in opposite directions. These batteries have a major safety issue – the liquid electrolyte can catch fire at high temperatures.

A promising alternative is solid-state batteries that replace the liquid with a solid ceramic electrolyte and swap graphite with metallic lithium. Ceramic electrolytes perform even better at higher temperatures, which is especially useful in tropical countries like India. Lithium is also lighter and stores more charge than graphite, which can significantly cut down the battery cost.

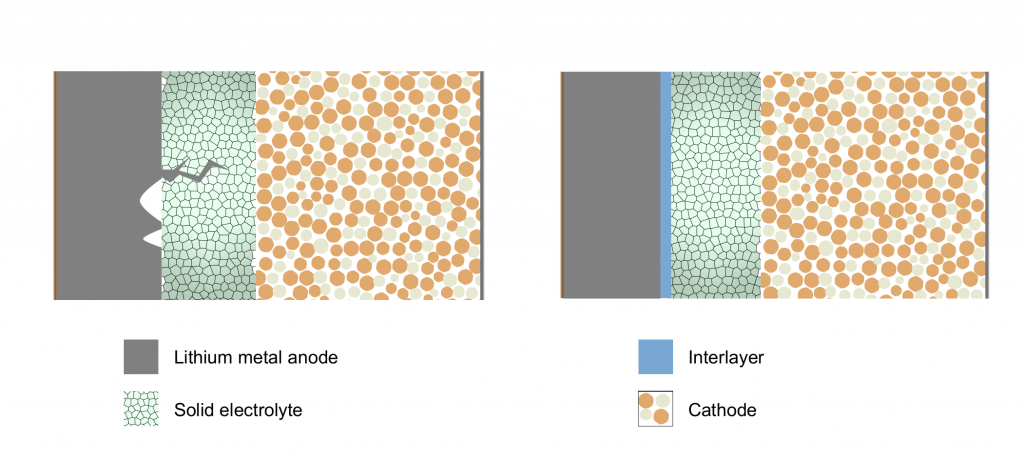

“Unfortunately, when you add lithium, it forms these filaments that grow into the solid electrolyte, and short out the anode and cathode,” explains Naga Phani Aetukuri, Assistant Professor in SSCU and corresponding author of the study published in Nature Materials.

To investigate this phenomenon, Aetukuri’s PhD student, Vikalp Raj, artificially induced dendrite formation by repeatedly charging hundreds of battery cells, slicing out thin sections of the lithium-electrolyte interface, and peering at them under a scanning electron microscope. When they looked closely at these sections, the team realised that something was happening long before the dendrites formed – microscopic voids were developing in the lithium anode during discharge. The team also computed that the currents concentrated at the edges of these microscopic voids were about 10,000 times larger than the average currents across the battery cell, which was likely creating stress on the solid electrolyte and accelerating the dendrite formation.

“This means that now our task to make very good batteries is very simple,” says Aetukuri. “All that we need is to ensure that the voids don’t form.”

To achieve this, the researchers introduced an ultrathin layer of a refractory metal – a metal that is resistant to heat and wear – between the lithium anode and solid electrolyte. “The refractory metal layer shields the solid electrolyte from the stress and redistributes the current to an extent,” says Aetukuri. He and his team collaborated with researchers at Carnegie Mellon University in the US, who carried out computational analysis which clearly showed that the refractory metal layer indeed delayed the growth of microscopic lithium voids.

Applying extreme pressure that can push lithium against the solid electrolyte can prevent voids and delay dendrite formation too, but that may not be practical for everyday applications. Other researchers have also proposed the idea of using metals like aluminium that alloy or mix well with lithium at the interface. But over time, this metal layer blends with lithium, becoming indistinguishable, and does not prevent dendrite formation. Raj explains how their technique differs: “If you use a metal like tungsten or molybdenum that doesn’t alloy with lithium, the performance which you get from the cell is even better.”

The researchers say that these findings are a critical step forward towards making commercial solid-state batteries a reality. Their strategy can also be extended to other types of batteries that contain metals like sodium, zinc and magnesium.