Are aerosols generated during routine eye procedures posing a risk to healthcare workers? Doctors at Narayana Nethralaya worked with IISc researchers to investigate

There is growing evidence that the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, could spread through aerosols – tiny droplets that can remain suspended in the air for hours in closed spaces. Aerosols can be generated during surgeries and out-patient procedures, lingering in the work environment of healthcare workers.

To investigate how aerosols are generated during routine eye procedures, doctors at Narayana Nethralaya, an eye hospital in Bengaluru, collaborated with researchers at IISc. They used high-speed imaging and aerodynamic models to visualise the generation of droplets during procedures such as cataract and LASIK surgeries.

“We identified the size of the droplets, and also calculated the speed and distance to which they travel,” says Saptarshi Basu, Professor at the Department of Mechanical Engineering, and co-author of two papers published in the Journal of Cataract and Refractive Surgery. The studies showed that during most procedures, aerosols are not generated, he adds.

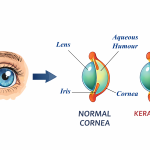

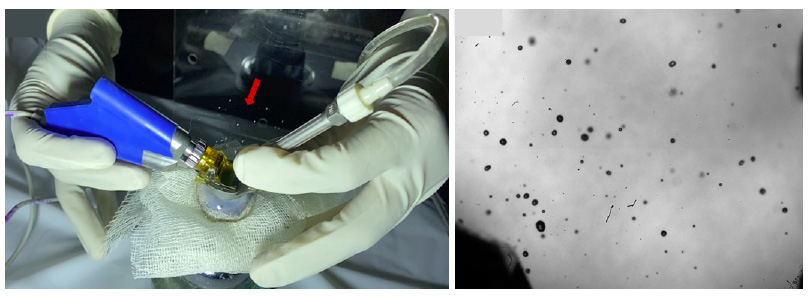

The first study focused on phacoemulsification, a type of cataract surgery in which an ultrasonic needle is used to break up the cataract. The fluids are then suctioned out and the eye is rehydrated with a balanced salt solution.

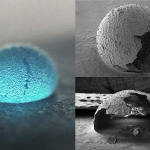

The needle and a sleeve carrying the salt solution are usually combined into a single disposable probe. In the study – conducted during surgeries on humans and animal eyes in a closed chamber – the researchers employed a technique called shadowgraphy, which uses a light source such as pulsed laser or LED to cast shadows of fast-moving droplets onto the sensor of a high speed camera.

As long as the probe was restricted to the inner layer of the eye called anterior chamber – a protocol normally followed – no aerosols were generated. Aerosols were formed only when the probe was exposed to the salt solution on the eye’s outer surface called cornea. Therefore, replacing the salt solution with more gelatinous or viscous materials can prevent fluid spurting and aerosol generation, the researchers say.

The second study investigated LASIK surgery, performed to correct near- or far-sightedness. It uses an oscillating blade to cut and lift a thin flap from the cornea’s top layer to reshape the inner layer called stroma. As the blade cut through to the stroma, some droplets were generated, likely due to the balanced salt solution used as a lubricant prior to the procedure. However, most of them were large in size (>90 micrometers) and therefore likely to settle down fast, reducing the risk that they will become aerosolised. Because the droplets were found to travel up to 1.8 m in a simulated surgery setting, adequate precautions should be adopted by doctors, the researchers suggest.

Based on these findings, the hospital has identified and implemented specific safety protocols, says corresponding author Abhijit Sinha Roy, Chief Scientist at Narayana Nethralaya Foundation. It has also put together videos to educate patients, medical staff and the general public, to make them feel more comfortable about resuming routine procedures.

“Because of COVID-19, a lot of other surgical procedures are getting delayed. Our concern is that patients should not end up compromising their vision just because they delayed getting the appropriate healthcare they needed. They should feel at ease after seeing these robust studies and safety measures implemented in our eye clinics,” he says.

Similar studies are also planned for orthopaedic and heart surgeries, says Basu.