Deepak Subramani’s work uses data science to take on geoscience and ecological challenges

It was 2009. Deepak Subramani was in the second year of his five-year dual degree (BTech and MTech) in Mechanical Engineering at IIT Madras when he visited IISc as part of a summer research fellowship. He was working in the Department of Mathematics under Rajeeva Laxman Karandikar, a visiting faculty member at IISc. A chance interaction led to a meeting with J Srinivasan, Professor at the Center for Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences.

Noting Deepak’s interest in computational modelling, Srinivasan put him in touch with C Balaji from IIT Madras who was working on atmospheric modelling, weather research and forecasting simulations. It set the young man from Thrissur on a journey that culminated in him returning full circle to IISc nine years later as an Assistant Professor in the Department of Computational and Data Sciences.

During the time in between, Deepak finished his dual degree at IIT Madras, went to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) to pursue a Master’s in computation for design and optimisation, and a PhD in Mechanical Engineering and Computation.

His career progression coincided with Artificial Intelligence entering the field of geophysical modeling. Deepak started his journey in the world of systems modelling by working on paths for autonomous underwater vehicles.

“I developed an algorithm to do path planning that optimally guides underwater robots from point A to point B,” he explains. He soon graduated to modelling entire systems, such as oceans and the atmosphere.

“Modelling whole environments is a very fascinating subject,” Deepak says. “This is part of something called nonlinear dynamics and chaos, and the relationships are highly complicated. We have some understanding of the physical processes that govern these systems, like gravity. In the atmosphere and ocean, in addition to gravity, the rotation of the earth also plays a very important role. Then there is the density of the water or the clouds in the air. So, now we need to model each and every part of the system, write equations that govern their movement in space and time, and solve them.”

This is akin to designing a game or a virtual world. The world has to be governed by certain laws – game physics as they say – which underpin actions and reactions within the system. Think of the movie The Matrix. In the simulated environment that is 20th century USA, the protagonist Neo is able to fly and slow down time because he can see the codes and manipulate the rules of the computer program. But the program Matrix is a system designed with parameters exactly like those of Earth. In the real world, scientists create similar virtual replicas of environments to study how different factors can drive different processes.

“We are modeling ocean and atmospheric flows,” Deepak explains. “We need to be able to predict when the monsoon will start. Getting the correct process dynamics is very difficult. In addition to our physical understanding of the process, we have instruments that give us data. So, now we blend physical understanding with the data and create prediction systems.”

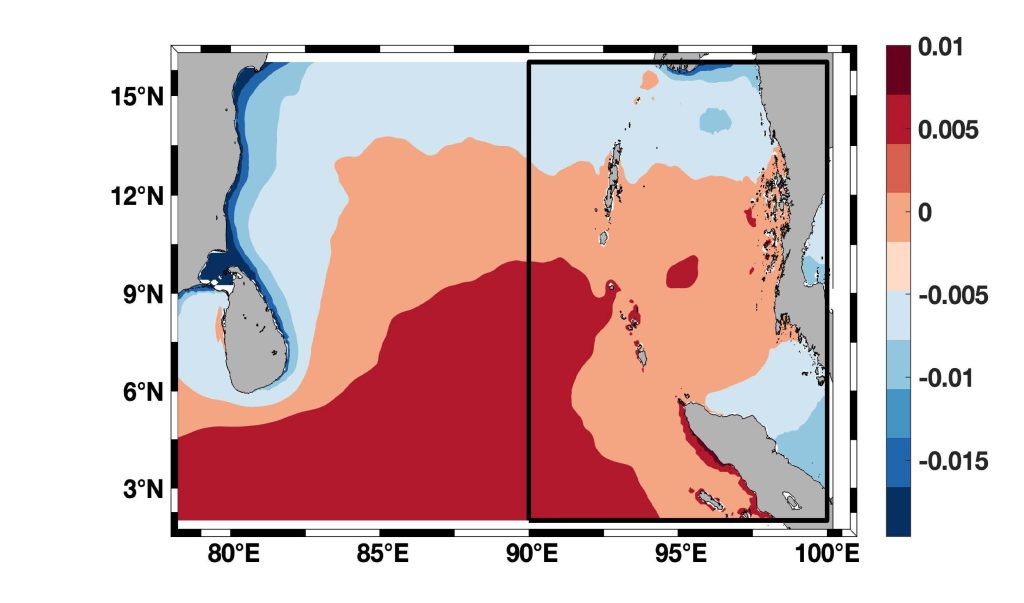

What Deepak enjoys most about modelling is that it is problem-agnostic – it can be applied to any challenge in any domain that needs a computational or data science solution. In 2016, Deepak was modeling temperature, salinity and biological content in the ocean when he received a fellowship from the Tata Centre for Technology and Design at MIT to work on solutions for sustainable fishing in India. For two years, Deepak worked with collaborators at the Dakshin Foundation, the India National Center for Ocean Information Services in Hyderabad, and the National Institute of Ocean Technology in Chennai.

“They wanted to ensure that coastal fisheries don’t collapse. We wanted to use ocean models to predict where the fisherfolks could go and fish would be and then distribute these areas to them through a quota system,” Deepak explains. His team divided the ocean into potential fishing zones, based on temperatures and salinity conditions in which fish like to live, and how they vary with individual species. Using this data, they were able to predict suitable fishing ecosystems and provide fishing zone advisories.

Deepak’s current research at CDS straddles three areas: computing, data science, and dynamics. Research problems at the intersection of any of these two pique his interest, he says. His lab focuses on developing and applying machine learning and artificial intelligence solutions to ocean and atmospheric modelling problems, autonomous routing and socio-technical systems.

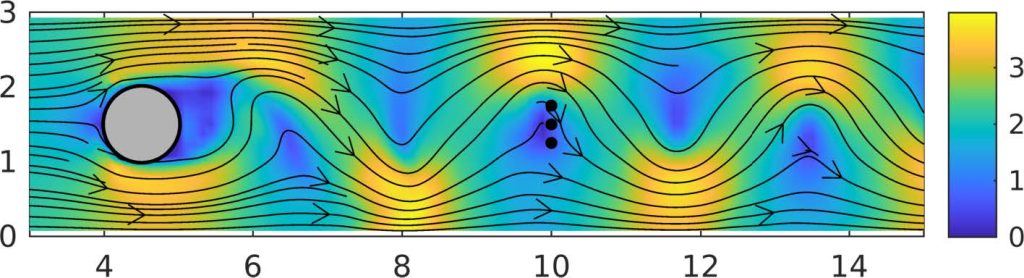

For example, deciding which paths autonomous underwater vehicles take has implications for moving strategic and defense equipment efficiently across the ocean. Similarly, his lab has also worked on software that can control robots that perform inspection missions in a shipyard. His students are working on simulating turbulent flows in wind farms to accelerate the energy transition. For such projects, the team develops both theoretical models and algorithms to find data science solutions.

Deepak also narrates how he took an interesting detour into ecological modelling. When he joined IISc, Kartik Shanker, Professor at the Centre of Ecological Sciences and cofounder of Dakshin Foundation, who had worked with him on the fisheries project, reached out to discuss extending the modelling process to other areas. They specifically wanted to find a solution for the human-elephant conflict in the Agasthyamalai region of the Western Ghats.

“The idea was to explore an agent-based model, which is a type of modeling framework in computation that simulates individuals as agents with some cognition and movement in a region,” explains Deepak. “So here, elephants and humans are the agents, and the environmental conditions are locations of the plantations, roads, rivers, hills, and slopes. Then there are ecosystem conditions such as dryness, wetness, temperature and so on. The elephants are radio-collared, and we get the movement pattern and relocation data. From that, we built a model for the elephants’ movement.”

The project helped the team track crop-raiding activities by elephants and how they change with movement patterns, weather conditions, animal aggression and food availability.

With diverse projects going on, Deepak says that he has little time to focus on his hobbies. The few minutes in his car while commuting to campus every day are the only time to explore new music or podcasts. His office – structured and scantly decorated – and life is designed for maximum efficiency.

Teaching also figures prominently in his work at IISc – apart from regular courses for undergraduate and graduate students, he teaches applied data science, machine learning and artificial intelligence to working professionals through the Center for Continuing Education. He was one of the recipients of IISc’s Excellence in Teaching Awards in 2022.

His passion, he says, lies in translating his research to the real world in order to find ways to help society. “Everything is about how to use computing and data science for social good – creating models that decision makers can use to form intelligent, sustainable decisions.”