New Centre aims to foster much-needed research on – and awareness about – these life-saving concoctions

“Animal venoms are absolutely fascinating,” says Kartik Sunagar, Assistant Professor at the Centre for Ecological Sciences (CES), IISc. These protein cocktails produced by snakes and other creatures can both kill and save lives – in fact, antivenom is made from these lethal mixtures.

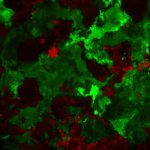

Kartik’s Evolutionary Venomics lab at CES has been studying venomous animals, their evolutionary history and the make-up of their venoms for many years. The work that the lab has done in collaboration with others across the country has revealed several shortcomings of commercially available antivenoms in treating snakebites. They have also found that the toxicity levels in snake venom differ based on where the snakes are located – and can even vary within the same species and in the same individual over its lifespan.

Venom scientists like Kartik and others in India have long felt the need for comprehensive efforts to document this diversity in venoms and standardise the production of antivenoms. For example, the same antivenom is used across the country to treat bites, whether they are from a cobra or a krait, without any regard for the differences in the venom composition. Experts believe that there is an urgent need for antivenom manufacturers, public health officials and policy makers to come together in order to develop region-specific antivenoms, especially for some of the neglected but dangerous species.

Those efforts have now received a shot in the arm with the establishment of a first-of-its-kind Antivenom Research and Development Centre in Bengaluru, with support from IISc, the Institute of Bioinformatics and Applied Biotechnology (IBAB), and the Government of Karnataka.

The Centre, which is coming up at Electronic City, is being built at an initial cost of Rs 7 crore. CN Ashwath Narayan, the Minister of IT-BT, Science and Technology, Government of Karnataka, laid the foundation stone for the Centre on 4 July 2022. In his inauguration speech, he pointed out how India is considered the global capital for snakebites and how there is a vast knowledge gap that exists in the field of venom research in the country.

Every year, 58,000 people die and 1,74,000 suffer permanent disabilities from snakebites, yet it remains the most neglected tropical disease. The antivenoms currently available in the market are largely ineffective as they are exclusively produced against the “big four” Indian snakes: the spectacled cobra, common krait, Russell’s viper and saw-scaled viper. However, India is home to many other venomous snake species whose bites can also be fatal and/or crippling. “Our Indian snakes and other venomous animals are really amazing and completely unexplored,” says Kartik. Currently used antivenoms are poorly designed and very few checks are in place to test the effectiveness of these drugs before they are released to the market.

To combat this problem, the new Centre will focus on carrying out research and improving the efficacy of antivenoms and related therapeutic drugs. Labs will be created where researchers from both IISc and IBAB can collaborate on research related to venoms and antivenoms. “This collaboration is extremely valuable and it will open up a lot of opportunities to initiate work in this area,” says Subramanya Hosahalli, Director of IBAB. The centre will work with major Indian antivenom manufacturers and help them improve their products, as well as offer venom and antivenom testing services. “We are also going to establish a standard of certification for venom quality and antivenom products, which will be useful for the industry,” adds Subramanya.

Education and outreach will be another important focus of the upcoming Centre. Both Kartik and Subramanya hope that such a Centre will inspire the next generation of herpetologists – scientists who study reptiles and amphibians – in India. The biggest attraction is expected to be a state-of-the-art serpentarium housing many species of snakes and other venomous animals like tarantulas, redback spiders, scorpions and endemic spider and centipede species, which will be open to the public, particularly the student community. “A kid can stand next to a vivarium and observe these enigmatic animals in near-natural habitats. They will also be able to watch through large glass windows the venom extraction process from a plethora of animals,” explains Kartik.

The Centre will also be a hub for key stakeholders like the forest department, clinicians, farmers and other members of local communities in snake habitats. They would have the opportunity to visit the Centre, study the snakes at the serpentarium, and gain hands-on experience in identifying and handling different species and administering first aid for snakebites, through targeted training programmes offered by the Centre. Kartik points out that clinicians themselves are not well trained in identifying snake species (or handling snakebites, in some cases) as most medical textbooks dedicate only half a page or one page to snakebites. “There are very few clinicians who are experts in treating and managing snakebites because that’s not part of the main curriculum in medical education,” says Subramanya.

Although antivenom research will be the ultimate focus, there are also plans to set up an incubation centre that will act as a springboard for startups that will prioritise venom research from a therapeutic perspective. Researchers at the Centre will also explore the curative benefits of venom for various other diseases – the kind of work that has never been done before in India, says Kartik. For example, captopril, a drug used to treat hypertension in the 1980s, was derived from the venom of the Brazilian viper, Bothrops jararaca. “Snakes have saved more lives than they have ever taken,” he adds.