The South Asia hub of Future Earth provides a platform to discuss and disseminate climate change solutions

Humans’ never-ending appetite for progress has ravaged the only planet that sustains us. Climate change, biodiversity loss, pollution, and population growth – all of these are accelerating at an alarming pace. They threaten ecosystems, wildlife, and human health. These threats need to be addressed at the global level, using data and science to increase awareness, engage and mobilise political leadership, and bring about transformative solutions.

It is in this context that the ‘Future Earth’ programme came into existence. It was first announced in June 2012 at the UN Conference on Sustainable Development (Rio+20), as a global initiative to strengthen the interface between policy and science. Under this initiative, diverse people from academia, policy, businesses, industry and civic society meet and discuss to come up with possible solutions for challenges posed by global environmental change.

Before Future Earth was established, there had been some programmes that sought to track how Earth systems change. An example is the International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme (IGBP) which spent 30 years tracking different physical, chemical and biological processes. But when Future Earth was set up, such programmes were brought into its fold. Future Earth was then divided into different regional administrative units to efficiently manage its operations across various countries. One of its global secretariats is now hosted at the Divecha Centre for Climate Change (DCCC), IISc.

“Being an active member of IGBP, we had submitted a proposal to host a regional office at our Institute concerning Future Earth’s operations in South Asia. It got accepted in 2016 and we inaugurated the South Asia regional office, with its domain spanning SAARC countries, Myanmar and the Indian Ocean Island countries (Mauritius and Maldives),” says SK Satheesh, Chair of DCCC and Director of the South Asia regional hub of Future Earth. “After five years of successful completion, we upgraded to a global secretariat hub – one of the nine global secretariats of Future Earth.” The Future Earth South Asia hub is supervised by a governing board.

Each global secretariat is tasked with generating its own reports about the current state of the environment. The hope is that such assessments can help scientists evaluate the impact of climate change at different scales and aid in achieving various sustainable goals.

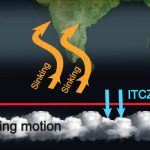

The South Asia global secretariat at IISc hosts several programmes and initiatives. One of them is a project called the Monsoon Asia Integrated Research for Sustainability (MAIRS). Major landscape features like vegetation, soil and water systems in the South, Southeast and East Asian regions have developed in a monsoon climate. In addition to having high population densities, these areas bear the brunt of variable and unpredictable monsoons, which cause frequent floods, droughts and heat waves. MAIRS aims to understand the impact of human activities on these climatic conditions and how such impacts will further affect socio-economic development in Asia. It also focuses on understanding how societies can mitigate or adapt to these changes by regulating law and policy.

Another initiative is the Water Solutions Lab Bengaluru (WSLB), established in 2017 to offer comprehensive water system diagnostics and new solutions for water-related issues. WSLB is divided into different groups. The water quality group looks into how pollutants like arsenic, fluorides, heavy metals, and so on contaminate water resources. The urban water group assesses the water resource base in Bengaluru and tries to address the risks and impact of water scarcity in different wards. The lake governance group studies the restoration of lakes (especially man-made ones) across Bengaluru. Yet another group analyses the equity of water consumption and distribution, especially in slums of the city.

In September 2019, a major international conference – the largest conducted by the hub – was organised, titled “Towards a Sustainable Water Future.” András Szöllösi-Nagy, Chair of the International Water Future Programme and former Governor of World Water Council, and Satheesh were the co-chairs of this conference. Participants included high-level policy makers, including ministers and parliament members from various countries, eminent scientists, and pioneers in water-related institutions and industries. The conference brought together the water science community to share available information, contribute ideas and action plans, and create innovative solutions to meet the sustainable development goals (SDGs) over the next decade. The frequent phenomena of extreme events and urban water crisis were identified as two areas of great concern to the scientists, stakeholders and the general public. This conference sought to develop a plan of action to implement solutions and tackle these events.

A third programme, called FoHCoS, was started in 2020 to drive conversations around food security (‘Fo’), health sensitisation (‘H’), coastal risks and resilience (‘Co’), and sustainable communities (‘S’) in South Asia. “We try to brainstorm and ask questions like: What are the various solution pathways? How can we prepare citizens for future disasters? The idea is to come up with solutions and express these to policymakers and all stakeholders involved. We plan to form working groups across countries,” explains Smriti Basnett, Deputy Director at the South Asia regional hub at DCCC. “Our strength lies in convening and getting people together to talk, because only when they start talking, maybe after some years, you’ll find the ripple effect of policies getting translated to implementation,” she adds.

Another aspect that the South Asia hub focuses on is science outreach – how to communicate the relevance of these initiatives to policymakers and the general public. Satheesh says, “We explain complex science topics using simple illustrative diagrams and send them to all universities, schools and colleges. Then, there’s policy briefings for policymakers. We send these to various ministries and departments at both central and state levels.”

Different events are conducted throughout the year. One example is the Indian Technical and Economic Cooperation (ITEC) programme of the Ministry of External Affairs. To enhance interactions with scientists from developing countries, Future Earth and DCCC conduct training programmes on “Climate Change and the Environment”. Recently, a two-week ITEC programme was conducted for a group of mid-career government officials from African, Latin American, South and Southeast Asian countries. Another workshop on data and tools for climate resilience planning was also organised, involving researchers, NGOs and government organisations.

Participants in such programmes are diverse, from scientists, bureaucrats, and ministers to farmers and school children, Satheesh says. “It’s a combination of all stakeholders because in any issue related to climate change, one particular section of society can’t contribute or get affected solely. You have to bring in multidisciplinary expertise.”

National quiz competitions are also conducted for school students from all over India at various levels covering different topics related to environment and climate change. These competitions have attractive cash prizes for the winners and are telecast by TV stations like Doordarshan. Satheesh, who acts as the quizmaster in the pre-final and final rounds, adds, “The whole purpose of this exercise is to create awareness among school students because they are the ones who will eventually face the consequences of climate change after, say, 20 or 30 years. They need to know why there’s a need to control emissions and resort to eco-friendly practices, and how their contribution to the cause matters in the long term.”