Trapping and studying them can provide insights into how material properties are influenced by electron interactions

Researchers at IISc have experimentally shown the existence of two species of few electron bubbles (FEBs) in superfluid helium for the first time. These FEBs can serve as a useful model to study how the energy states of electrons as well as the interactions between them in a material influence its properties.

The team included Neha Yadav, a former PhD student at the Department of Physics, Prosenjit Sen, Associate Professor at the Centre for Nano Science and Engineering (CeNSE) and Ambarish Ghosh, Professor at CeNSE. The study was published in Science Advances.

An electron injected into a superfluid form of helium creates a single electron bubble (SEB) – a cavity that is free of helium atoms and contains only the electron. There are also MEBs – multiple electron bubbles that contain thousands of electrons.

FEBs, on the other hand, are nanometre-sized cavities in liquid helium containing just a handful of free electrons. The number, state and interactions between free electrons dictate the physical and chemical properties of materials. Studying FEBs, therefore, could help scientists better understand how some of these properties emerge when a few electrons present in a material interact with each other.

According to the authors, understanding how FEBs are formed can also provide insights into the self-assembly of soft materials, which can be important for developing next-generation quantum materials. However, scientists have only theoretically predicted the existence of FEBs so far. “We have now experimentally observed FEBs for the first time and understood how they are created,” Yadav says. “These are nice new objects with great implications if we can create and trap them.”

Yadav and colleagues were studying the stability of MEBs at nanometre sizes when they serendipitously observed FEBs. “It took a large number of experiments before we became sure that these objects were indeed FEBs. Then it was certainly a tremendously exciting moment,” says Ghosh.

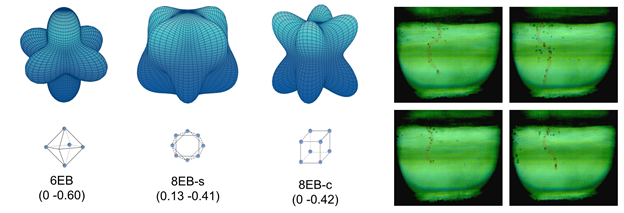

The researchers first applied a voltage pulse to a tungsten tip on the surface of liquid helium. Then they generated a pressure wave on the charged surface using an ultrasonic transducer. This allowed them to create 8EBs and 6EBs, two species of FEBs containing eight and six electrons respectively. These FEBs were found to be stable for at least 15 milliseconds (quantum changes typically happen at much shorter time scales) which would enable researchers to trap and study them.

“FEBs form an interesting system that has both electron-electron interaction and electron-surface interaction,” Yadav explains.

There are several phenomena that can be deciphered through FEBs, such as turbulent flows in superfluids and viscous fluids, or the flow of heat in superfluid helium. In the same way that current flows without resistance in superconducting materials at very low temperatures, superfluid helium also conducts heat efficiently at very low temperatures. But defects in the system, called vortices, can lower its thermal conductivity. Since FEBs are present at the core of such vortices – as the authors have found in this study – they can help in studying how the vortices interact with each other, and how heat flows through the superfluid helium.

“In the immediate future, we would like to know if there are any other species of FEBs, and understand the mechanisms by which some are more stable than the others,” Ghosh says. “In the long term, we would like to use these FEBs as quantum simulators, for which one needs to develop new types of measurement schemes.”