Researchers at IISc have designed a synthetic compound (antigen) that can latch on to a protein in blood and hitchhike a ride to the lymph node, where it can boost the production of antibodies against cancer cells.

The approach gives a new direction to develop vaccine candidates for a variety of cancers, the researchers say.

Inside the human body, cancer cells can weaken or shut down the production of antibodies that target and eliminate them. Developing a cancer vaccine, therefore, involves modifying or creating a mimic of an antigen found on the surface of cancer cells to turn up or turn on this antibody production. In recent years, scientists have turned to carbohydrates found on cancer cell surfaces to develop these antigens.

“Carbohydrate-based antigens have enormous importance and relevance in cancer vaccine development,” explains N Jayaraman, Professor at the Department of Organic Chemistry and senior author of the study published in Advanced Healthcare Materials. “One major reason is that both normal and abnormal [cancer] cells have large amounts of carbohydrates coating their surfaces. But the abnormal cells carry carbohydrates that are very heavily truncated.”

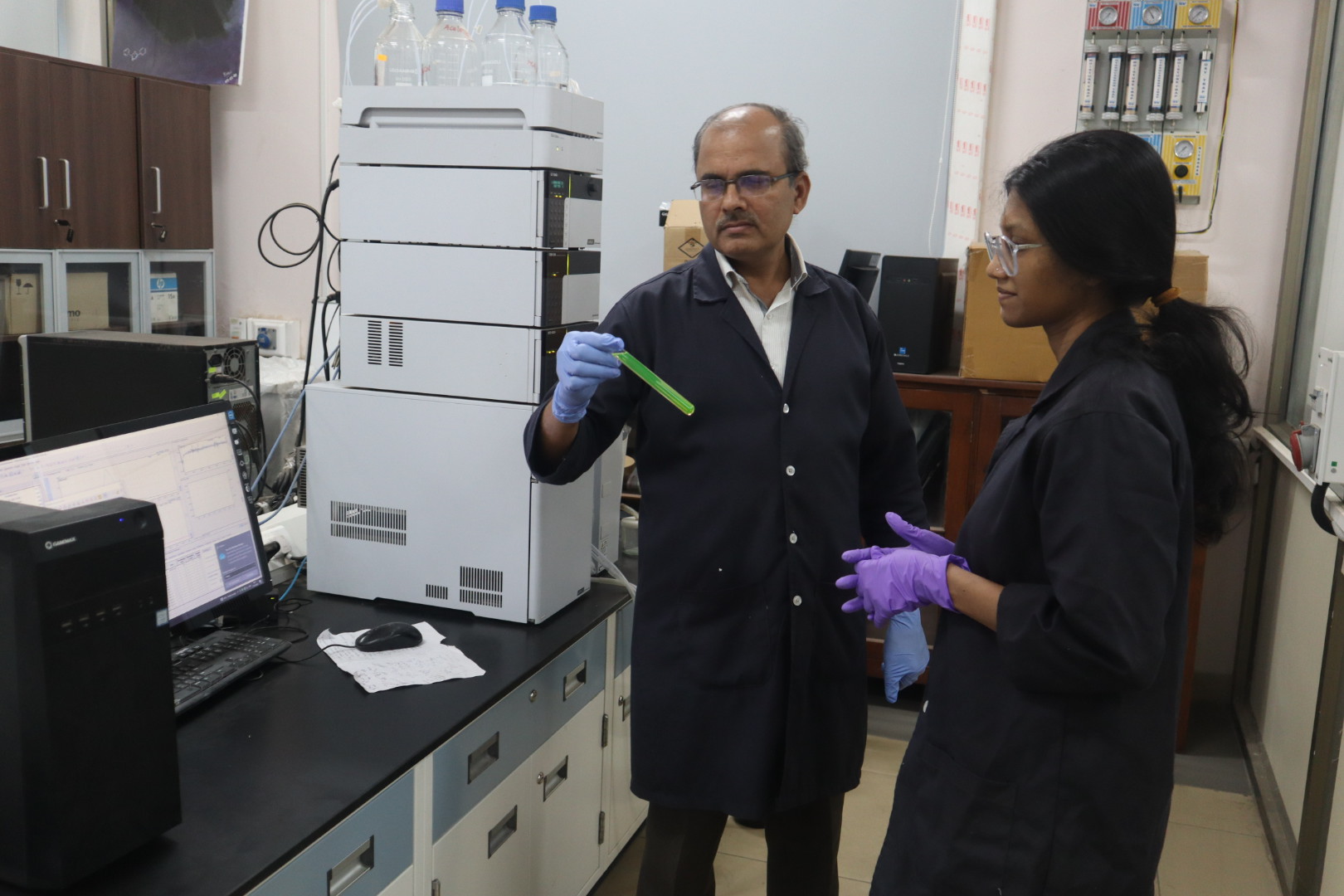

(Photo: NJ Group/IISc)

Scientists have earlier tried ferrying such antigens into the body using an artificial protein or virus particle as the carrier. But these carriers can be bulky, lead to side-effects, and sometimes reduce antibody production against cancer cells. The IISc team, instead, decided to exploit the carrying ability of a natural protein called serum albumin, the most abundant protein in blood plasma.

To design the compound, Jayaraman and his PhD student, Keerthana TV, zeroed in on a truncated carbohydrate called Tn found on the surface of a variety of cancer cells, and synthesised it in the lab. Then, they combined it with a long-chain, oil-loving chemical – unlike carbohydrates which are water-loving – to form bubble-like micelles. They found that the combination is able to bind strongly to human serum albumin.

“The moment it latches on to albumin, the micelle breaks, and all the individual [antigen] molecules bind to the available albumin,” Jayaraman explains. “This opens up the idea that one doesn’t necessarily need to search for a virus or a protein or other types of carriers. Serum albumin is sufficient to carry it forward.”

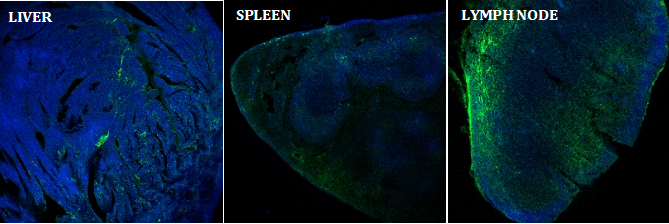

The researchers injected the compound into mice models to track its uptake and effect on the immune response. They found that the antigen accumulated largely in lymph nodes, the sites of key cellular mechanisms involved in the body’s immune response, including the activation of killer T cells and antibody production.

Mice immunised with the compound produced higher levels of antibodies, even at low doses, than those given a similar antigen ferried in via an alternative external protein carrier. The researchers found that a second immunisation shot with their compound led to much higher levels of antibody production than the first immunisation. This could be due to the activation of immune cells called memory B cells created during the first shot, which further boosts the production of antibodies, they suggest.

The team is hopeful that the compound can be taken forward for vaccine development and clinical trials. Jayaraman adds that the method can, in principle, be adapted for other types of vaccines as well.

“The Tn antigen is present on almost all cancer cells, including breast cancer and prostate cancer cells,” says Keerthana. “By changing the type of antigen, we can target multiple cancers.”