Unique initiative seeks to investigate ageing in the Indian population

It is a sunny August morning and the Biological Sciences building at IISc is abuzz. People are lining up at the registration desk and standees from startups cover the hallway. They are here for the Deep Science and Technology Industry Conclave, organised by the newly launched Longevity India initiative at IISc.

In his opening address, Deepak Saini, convenor of Longevity India and Professor at the Department of Developmental Biology and Genetics (DBG) makes a compelling case for ageing research. He points out how India’s current population is largely young, which means that in the future, they will all grow old, potentially becoming a societal burden. “Are we addressing this need for tomorrow?” he asks.

In the audience are a mix of researchers, industry representatives and startup founders, who have come together to exchange views and research findings on ageing. Topics range from ageing biomarkers and therapeutics to wellness and lifestyle interventions. One of the goals of the conclave was to shine a light on not just ageing, but also “healthy ageing.”

Ageing is a complex process of gradual deterioration through which cells lose their function and ultimately die. A major debate in the field of ageing research has been whether or not it is possible to extend humans’ lifespan – some scientists believe that we may have reached an upper limit to how long we can live. Studies in recent years have pointed to how life expectancies around the world are slowing down. The focus, therefore, has started shifting towards geroscience – a new field of research that looks at extending the “health span” or the number of years people can spend in good health.

In India, Deepak points out, people generally accept ageing as something that is inevitable. Diagnosing and treating diseases has been the priority. But in recent years, Deepak sees a shift in the healthcare landscape to assessing the well-being of even healthy individuals.

The Longevity India initiative was born out of this interest in healthy ageing among several faculty members at IISc. It seeks to understand diverse aspects of ageing, from fundamental biology of how cells age to translational research – developing products and solutions for ageing-related challenges, and technologies that can improve the quality of life. It also involves outreach activities like research webinars, a monthly newsletter, and events and conferences aimed at promoting awareness and interest in ageing research and technological developments.

“In India, technological innovation in ageing is very nascent,” says Suramya Asthana, lead coordinator at Longevity India. “The longevity supplement market is largely unregulated, with little evidence of true anti-ageing effects. Reliable biomarkers of ageing are scarce, and many have been derived from Western populations, leaving us uncertain about their applicability to Indians.”

The initiative received initial funding from Prashanth Prakash, Partner at Accel India. Prashanth recalls that his own personal journey and interest in optimising his health got him to think about ageing. He believes that ageing needs to be viewed from a systems approach in which individual components such as physical health, metabolic health, mental health and nutrition are all interconnected. “Having an entity that can bring researchers, people in industry, and the medical fraternity all together on one platform to play a catalytic role to accelerate these healthy ageing solutions was much needed,” he says.

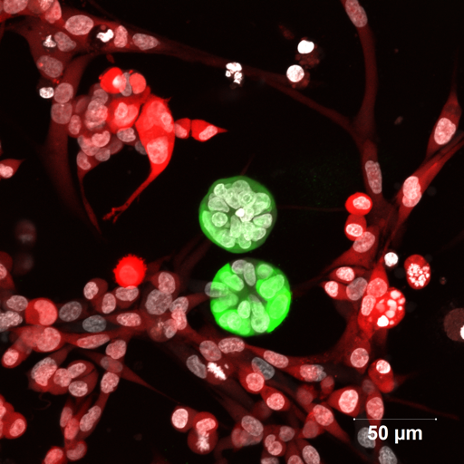

Longevity India was formally launched on 18 April 2024. One of its key activities is long-term projects that study ageing in healthy individuals. The first seeks to pinpoint age-related biomarkers in individuals of different ages, a project that involves multiple researchers at IISc and other institutes, in collaboration with doctors at Ramaiah hospital. It will focus on collecting samples of hair, blood, cells, and saliva from healthy individuals between the ages of 20 and 70. The data from this study can then be analysed using machine learning models to predict the overall wellness of the individual and identify specific organs that may be ageing faster than others. The second project aims at developing full-fledged models of organ systems with signatures of ageing, which could help understand how diseases like cancer spread in the body.

“Understanding ageing required a holistic multipronged approach unlike the current specialist approach. That’s why a multidisciplinary approach with multiple stakeholders is needed,” says Deepak.

Laying the groundwork

A key protein involved in regulating our energy metabolism is AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK). Research has shown that AMPK activation can delay ageing. When AMPK is activated, in turn, it activates autophagy in cells – a process in which abnormal, old and damaged proteins inside the cell are broken down and recycled. “By activating autophagy, AMPK may be able to remove the old, bad, accumulated muck from the cell and thus contribute to better ageing,” explains Anu Rangarajan, Professor at DBG.

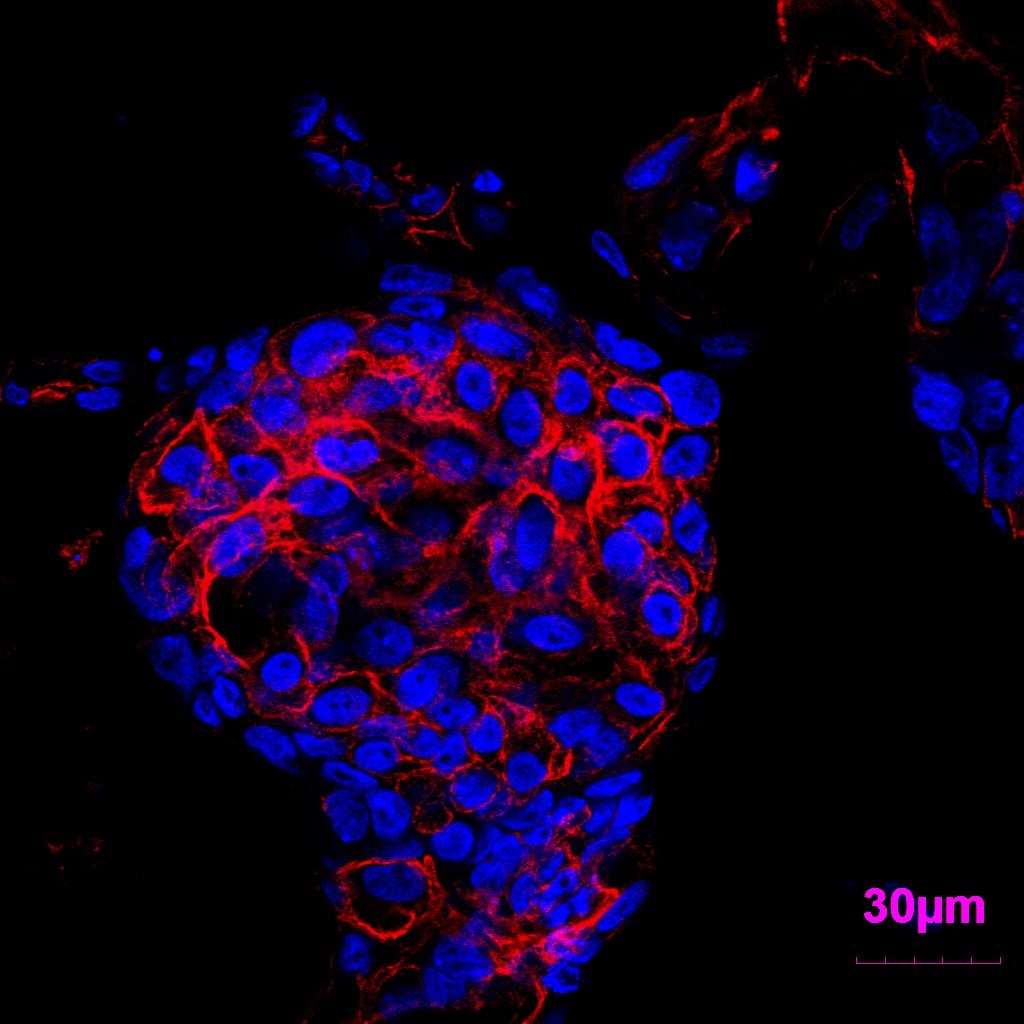

Under the Longevity India Initiative, her lab is looking at how signalling pathways of stem cells play a role in cancer initiation and, in some cases, relapse. “AMPK can be a good guy for ageing. But my own lab has shown AMPK activation promotes cancer, and autophagy helps this process!” she says. This is why Anu hopes to dissect distinct signalling pathways driven by AMPK to find out which contribute specifically to ageing and to cancer.

Cancer biologist Ramray Bhat, who is also part of the initiative, is intrigued by how ageing exacerbates and interferes with the management of cancer. “It is a very interesting problem for me,” says Ramray, Associate Professor at DBG.

Apart from the age-related biomarkers study that Ramray is part of, he has also teamed up with Prosenjit Sen, Professor at the Centre for Nanoscience and Engineering (CeNSE), to track mechanical properties of blood cells that change as a person ages.

In collaboration with other researchers in Longevity India, Ramray’s lab also seeks to establish models that mimic the ageing of cells lining various organs and inner cavities of our bodies. “Once we are able to build these model systems, we can start testing natural compounds, drugs, and nutraceuticals that can help slow down the ageing process within these organs and tissues,” he explains.

From lab to market

A key challenge that researchers like Ramray and Anu face is translating their work from the lab to the clinic. One way to circumvent bottlenecks is to have clinicians come in as part of the project even at the research design and conceptualisation phases, Ramray points out. “That will help make the study much more robust and stronger.”

There are also social challenges to overcome. “Sometimes patients take their files from the hospital which makes it hard for the doctors and researchers to follow up with them,” Anu says. Creating electronic records and mechanisms for following up with patients would be very beneficial, she adds.

A significant challenge is the availability of healthcare data from the Indian population. Ramray says that there needs to be concerted efforts to uncover the fundamental biology of ageing in the Indian population, given our diversity in population and genetic makeup. This gives us a unique opportunity, he says, to look at how the genes have mixed with migration, epidemiological, and environmental dynamics, and how this influences ageing.

“While western data points are available, they don’t extrapolate to Indians in a clean fashion,” Deepak adds.

Collecting such data is crucial because a 2024 report by the United Nations Population Fund says that 68% of the Indian population is between the ages of 15 and 64. This would mean that in another three decades, this entire young population is going to age, which might potentially bump up the number of cancer cases. “I’m very interested to know how, as an economy, we are going to cope with these increasing numbers,” Anu adds.

Prashanth points out that exhaustive data from the Indian population can help develop personalised solutions for ageing. Startups, he says, can help translate these solutions into products. “These industries will provide solutions to people wanting to do something in their 40s, 50s and 60s to have a functionally better 70s, 80s and 90s.”

More broadly, there is a need to shift away from looking at ageing as an illness, Deepak says. “It is a systemic state, not a disease.”