The human brain is a complex organ with over 80 billion neurons. But it can still trip up when it comes to multitasking. Trying to send an email at the same time as talking to someone can almost be enough to short-circuit our synapses, leaving us distracted and prone to making mistakes.

“The brain is a very large, complex, connected network, but even with simple things, bottlenecks happen. It’s very hard to do two unpractised actions at the same time,” explains Sridharan Devarajan, Associate Professor at the Centre for Neuroscience, IISc.

Sridharan has long been fascinated by attention – how our brain decides to focus on one specific object in front of us and not get distracted by other objects in the background. In two recent studies, his team has teased out distinct brain regions and mechanisms involved in our ability to pay attention. Such insights can help scientists better understand and treat attention-related brain disorders.

Until recently, scientists assumed that attention was a unitary phenomenon. But research in Sridharan’s lab and others’ has shown that this is not the case – we now know that there are at least two components or parts of attention that can be quantified, called sensitivity and bias.

“When you pay attention to something, the brain processes information from it better and extracts useful content from that information – this aspect of attention is what we call sensitivity,” explains Sridharan. “Bias is the brain deciding that some information is more important than others for making decisions.”

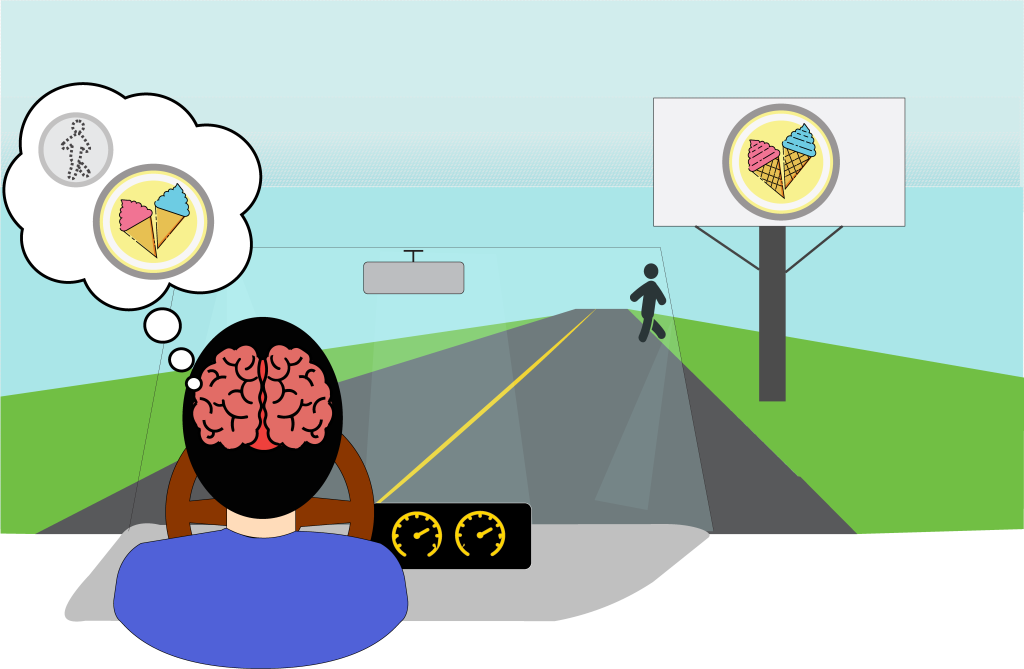

Imagine driving a car down a busy road (which is almost everywhere in Bengaluru). Your eyes may spot many different objects, bombarding your brain with myriad visual sensory inputs. But your brain chooses to focus on the car right in front of you. Therefore, it keenly tracks this car to pick out its every movement – this is sensitivity. Simultaneously, your brain decides that cars on the other lane are not important for your decision-making and selectively filters out information from them – this is bias.

In a recent paper published in Nature Communications, Sridharan and his group have shown that a particular region of the brain, called the right posterior parietal cortex (rPCC), specifically regulates the bias component of attention. They zeroed in on rPCC because clinical studies had shown that patients who suffered a stroke in this region completely neglected objects on one side of their visual world.

The group asked human participants to covertly view two objects on different sides of the screen, but attend to one of the sides indicated by a visual cue. Depending on how accurately and reliably the participants were able to make out the object’s features on the cued versus the uncued side, the researchers were able to quantify sensitivity and bias independently for each.

“A challenging aspect [of the project] was recruiting participants as volunteers,” says Ankita Sengupta, PhD student in Sridharan’s group and the lead author of the Nature Communications study. “There is a gap in the understanding of safety of neurostimulation techniques; we need to educate the general public about this.”

The team used non-invasive techniques called transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) to briefly disrupt brain activity in the participants’ rPCC. What they saw was that disrupting rPCC temporarily diminished the bias component in the participants.

In another paper in eLife, Sridharan’s team also tracked electrical activity (“neural signatures”) related to sensitivity and bias independently, using electroencephalograms (EEGs) recorded non-invasively from participants’ brains.

The researchers started out by trying to understand whether bias or sensitivity plays a major role during something called the “attentional blink” – when our brain is unable to process the second of two objects that it must track in rapid succession.

(Image courtesy: Swagata Halder and Deepak Velgapuni Raya)

“If you ask people to pay attention to a rapid stream of information and present them with multiple target objects that need to be attended to, when the first target comes up, they will register it. But if the second target comes up very soon after the first target, they will likely miss it,” explains Sridharan. “It’s just like your eyes blinking. It is almost as if the attentional system – once it receives a piece of information – blinks, and so the next piece of information cannot get in if it comes in too soon [after the first].”

The participants in this case were presented with black and white gratings tilted in different directions, one after the other. They then had to push buttons to answer questions about how these targets were tilted, all while their brain’s electrical activity was being recorded. The researchers analysed how well the participants were able to distinguish the second target that they were presented with. With the help of computational models, the team was able to tease apart the roles of sensitivity and bias during the attentional blink.

“Initially, we expected both components of attention – sensitivity and bias – to be impaired,” says Swagata Haldar, PhD student working in Sridharan’s lab and lead author of the eLife study. “To our surprise, we found that attentional blink affects mainly sensitivity, and not bias.”

Sridharan believes that understanding such phenomena can eventually help us treat attention disorders with more precision. Current treatments involve the use of strong medicines or drugs that can lead to abuse and side-effects. “If you really want to treat attention disorders, it could be risky to give psychostimulant drugs that will affect everything at the systemic level,” he says. “You have to know the pathways involved, the different components and pieces, and how the brain puts them together to create this phenomenon called attention. Then you can provide much more targeted treatments.”