How advances in screening are helping us better understand gene function

When you think of biology, the word ‘gene’ is bound to spring into your mind. From casual discussions of familial resemblance to more serious clinical assessments of health, genes have become central to how we make sense of life.

The term ‘gene’ was coined in the early 20th century by Wilhelm Johannsen. This was an era when Darwin’s theory of evolution and Mendel’s observations on inheritance were still hot off the press. As the ideas of natural selection and inheritance started to blend into a common framework, scientists began using the word ‘gene’ to denote a unit of inheritance responsible for an observable trait, known as a phenotype (the colour of one’s eyes, or the shape of a pea seed). This is still a common (and useful) definition.

But this early definition was rather abstract and did little to clarify what exactly a gene does to exert its influence. After World War II, fundamental research on genetics gained traction, and technical advances allowed us to dig deeper. The molecular description of DNA, embodied by the double helix model from 1953, paved the way for a more physical and functional description of the gene. Experiments through the mid-20th century showed that genes occupy a specific place on chromosomes and encode a related protein. These proteins are responsible for molecular functions within the cell, and lead to the emergence of observable traits.

Linking genes to proteins was a scientific milestone. Linking a gene to a trait, however, was more complicated. This process – establishing which gene is responsible for a trait – is known as ‘genetic screening’.

For a long time, genetic screening was quite laborious. “Even [until] 30 years ago, screening worked by inducing random mutations, and observing the phenotype,” explains Sachin Kotak, Associate Professor at the Department of Microbial and Cell Biology. By observing changes in the phenotype, and how these changes are passed on from parents to offspring, traits could be linked back to responsible genes.

For instance, if one were interested in the process of wing development in flies, thousands of flies would be exposed to mutation-causing chemicals, and flies that didn’t show proper wings would be examined. “[But] locating the gene which was mutated was a tedious job, taking 5-6 years,” adds Sachin.

Entire careers were spent on pinning down genes responsible for a certain trait. Even then, there was no guarantee that only one gene would be affected by the randomly acting mutagens. Humans have 20,000 genes. Studying each of these using classical screening methods is nightmarishly sluggish, not least because human cells are challenging to work with. Gaining useful genetic insights into life and illness at a molecular scale would take generations.

But things drastically changed in 1988. The USA government decided to fund a project that would transform the course of biology research and accelerate the understanding of our genetics – the Human Genome Project.

One of the most ambitious scientific collaborations in history, this effort set out to map the entire human genome. Driven by advances in sequencing – the process of piecing together the string of DNA – we were now able to “read” almost our entire genome in a matter of 13 years. This was the beginning of a massive shift in the field, the start of the genomics era.

“A major factor underlying this shift is that technology has evolved at a pace that we did not anticipate,” says Maya Raghunandan, Assistant Professor in the Department of Developmental Biology and Genetics. These technologies include Nobel-winning discoveries such as RNA interference (a process wherein RNA molecules can silence specific genes) and CRISPR (a revolutionary gene-editing technology allowing scientists to precisely cut, modify, or insert DNA sequences). They gave us tools to “silence” and activate individual genes at will. This has allowed us to manipulate an individual gene and directly link any change seen in traits back to that gene.

Inverting the process

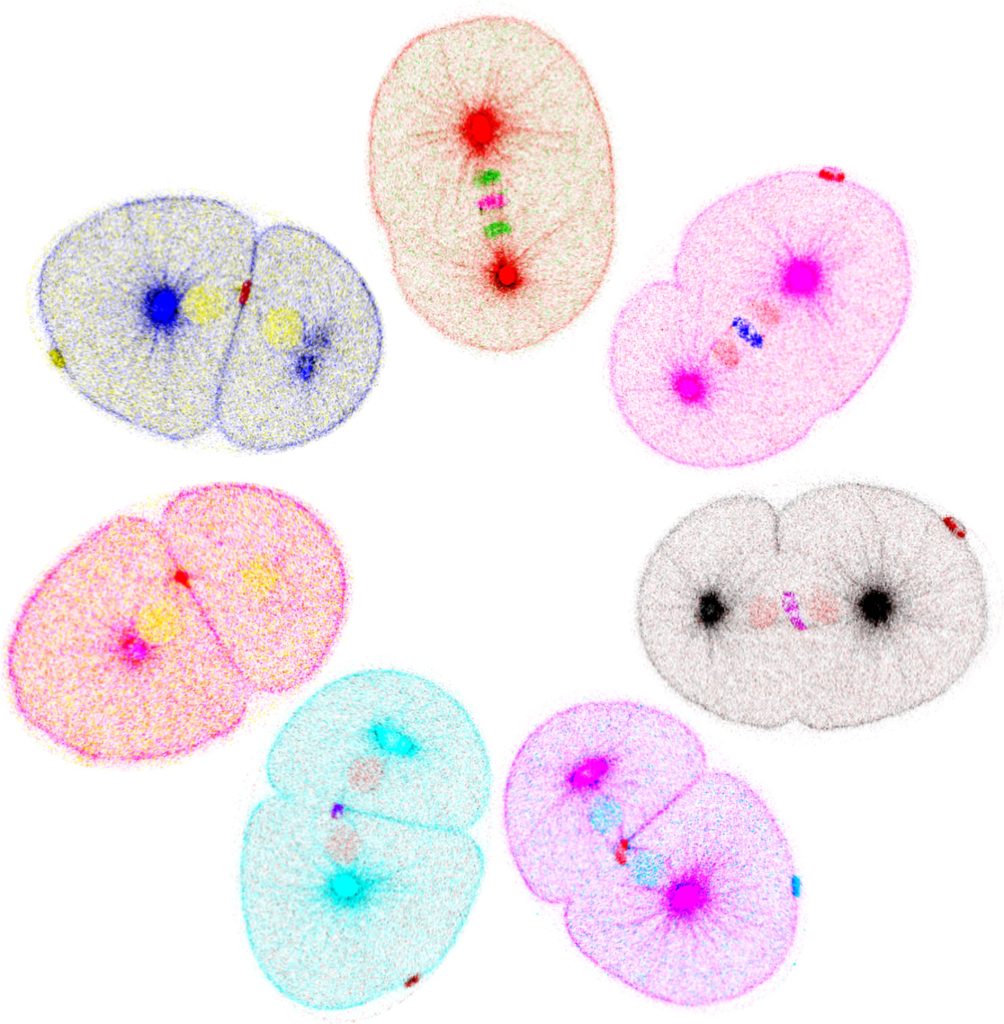

The ability to manipulate individual genes in a finely controlled manner is known as reverse genetic screening. Any phenotype or trait of interest, like the growth rate of a cancer cell, or the way an organism utilises nutrients, can now be studied at a molecular scale by individually changing a large number of genes.

Earlier screens relied on first randomly causing mutations, finding a trait of interest, and then searching for the causative gene – the process can take years. But reverse screens work backwards: They disrupt known genes individually and then watch for a changed trait, eliminating the mapping process. A modern high-throughput genetic screen – using advanced sequencing techniques – can identify the contributions of thousands of genes to a phenotype in a matter of weeks.

Interestingly, the sheer volume of genes examined has led scientists to uncover new roles for even known genes.

“Modern genetic screens allow us to examine multiple effects at the same time. With screens today, we often end up finding things that have no relation to the biology that we were originally studying. This helps us look beyond what we know. We sometimes end up finding a new function for genes which we hadn’t thought of before,” says Maya.

Crucially, the speed, scope, and relative simplicity of reverse genetic screens have set the stage for both fundamental and medically relevant discoveries. We now know the genes implicated in basic cellular processes such as cell division and metabolism – this knowledge is essential for understanding how such processes are misused by disease-causing viruses and bacteria. Multiple open databases which collate the results of thousands of screens now exist, such as DepMap, acting as an encyclopedia of genetic function for researchers.

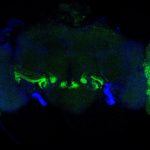

Screens have also become a valuable part of the molecular biologist’s toolkit. Sachin’s lab, which studies nuclear division during mitosis, uses RNA interference screens to make novel discoveries. For example, scientists had earlier thought that proteins called kinases – which work by tagging a phosphate group to membrane proteins to destabilise them – were essential in nuclear membrane breakdown. “[But] using genetic screens, we were able to show that another class of proteins which remove these phosphate moieties, called phosphatases, also play an essential role,” he explains.

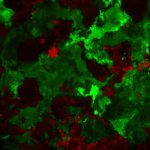

Another area in which these screens have found footing is oncology and personalised medicine. Maya’s lab, for example, seeks to use genetic screens to gain translational insights into an important yet understudied subset of cancer cells called ALT+ cells. Through a molecular pathway (ALT – Alternative Lengthening of Telomeres) that prevents the degradation of chromosome ends over time, these cells can essentially become immortal in principle. “Cancer cells, like viruses, evolve under selective pressure. Cells actively evade treatment by taking advantage of mutations that arise because of the treatment,” she says. “High-throughput screens are necessary to keep up with this pace of evolution.”

The first draft of the Human Genome Project came out in 2003. Efficient high-throughput screens that can truly scan the entire genome have only been around for as long as Wikipedia has. In this time, falling sequencing costs have made screens widely available. With refinements to CRISPR, we can now not just activate or deactivate genes, but make finer changes to their sequences. In addition to the functions of genes, we can thus now study the effects of mutations on their function.

However, a single gene can never tell the full story. The human genome is intricate, with genes being able to work with and compensate for a loss of each other. To widen our understanding, we must thus be able to manipulate and study multiple genes together – that’s where the next frontier lies.