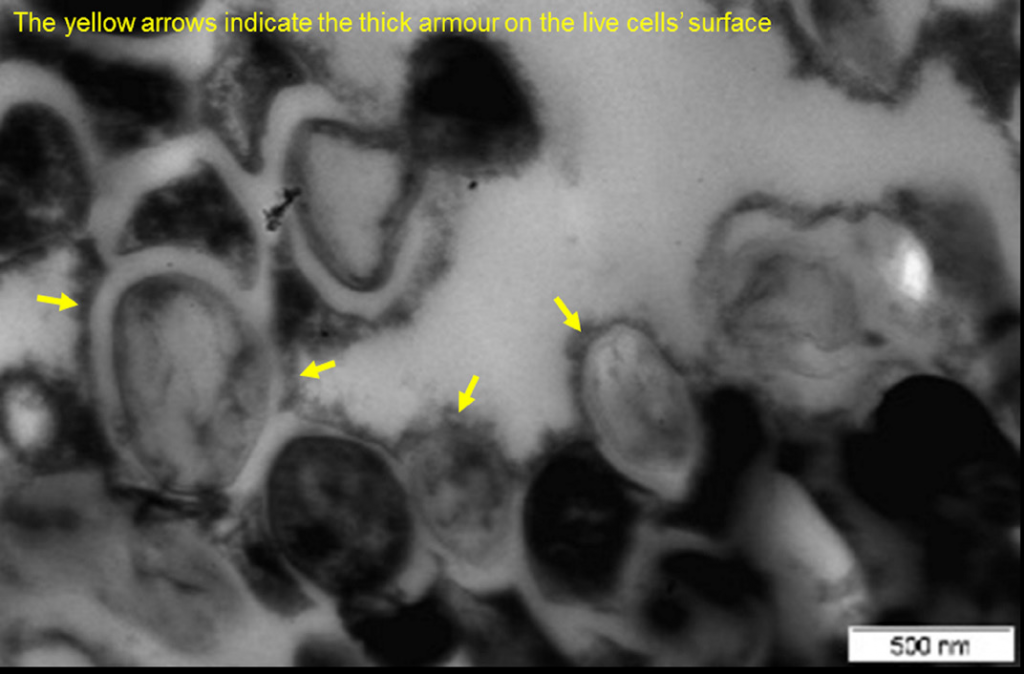

The bacterium that causes tuberculosis (TB) is notorious for gaining resistance to antibiotics, which makes treatment of the disease difficult. A new study by P AjitKumar and colleagues from the Department of Microbiology and Cell Biology shows that when TB bacteria encounter the common anti-TB drug rifampicin, a small proportion of the bacterial cells develop a thick, armour like capsule. This armour reduces the entry of the drug, thereby preventing the build-up of lethal levels within the cells. This strategy ensures the survival of these cells despite the continued presence of lethal levels of the drug outside.

The team also discovered that this capsule consists of certain types of carbohydrate molecules that make it difficult for rifampicin to enter the cells. The small amount of rifampicin that manages to enter the cells triggers a stress reaction, which in turn causes mutations in the bacterial DNA. In the subsequent generations, those bacterial cells that have gained rifampicin-resistant mutations escape antibiotic-mediated death. These mutant bacteria grow and divide to generate new populations of cells that are entirely rifampicin-resistant and therefore survive in the presence of lethal doses of the drug.

– with inputs from the authors