Pollutants like microplastics may be causing growth defects in fish in the Cauvery River, a new study in Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety reveals. The study was led by Upendra Nongthomba, Professor at the Department of Molecular Reproduction, Development and Genetics (MRDG).

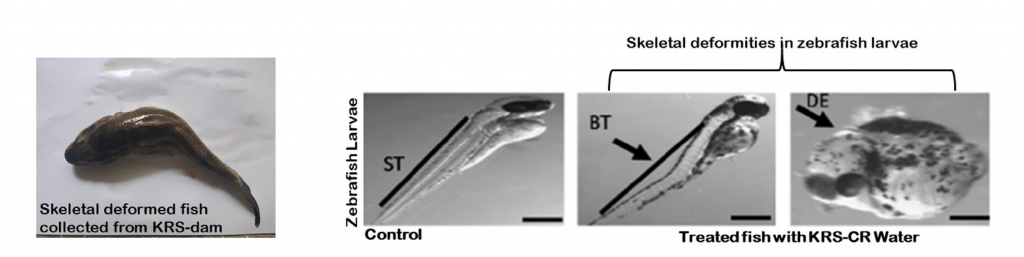

Nongthomba likes his fish. “Over the years, I have cherished going to the backwaters of the Krishna Raja Sagara [KRS] Dam and having fried fish on the Cauvery River bank,” he says. But in recent times, he has been noticing physical deformities in some of them. He began to wonder whether the quality of water may have something to do with it.

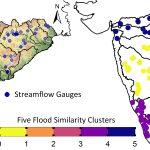

“Water is essential for everyone, including animals and plants. When it is polluted, it is capable of causing diseases, including cancer,” adds Abass Toba Anifowoshe, a PhD student in Nongthomba’s lab, and the first author of the study. Nongthomba’s lab, therefore, conducted a comprehensive study of pollution at the KRS Dam and its potential effects on fish. They collected water samples from three different locations with varying speeds of water flow – fast-flowing, slow-flowing, and stagnant – since water speed is known to affect the concentration of pollutants.

In the first part of the study, Nongthomba’s team analysed the physical and chemical parameters of the water samples. All but one of them fell within the prescribed limits – dissolved oxygen (DO) levels were much lower than they needed to be in samples collected from the slow-flowing and stagnant sites. Water from these sites also had microbes such as Cyclops, Daphnia, Spirogyra, Spirochaeta and E. coli, well-known bio-indicators of water contamination.

Using a technique called Raman spectroscopy, the researchers detected microplastics – minute pieces of plastic often invisible to the naked eye – and toxic chemicals containing the cyclohexyl functional group. Microplastics are found in several household and industrial products, and chemicals containing the cyclohexyl group are commonly used in agriculture and the pharmaceutical industries.

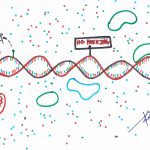

Next, Nongthomba’s team investigated whether pollutants in water could account for the developmental abnormalities seen in wild fish. They treated embryos of the well-known model organism, zebrafish, with water samples collected from the three sites, and found that those exposed to water from the slow-flowing and stagnant sites experienced skeletal deformities, DNA damage, early cell death, heart damage, and increased mortality. These defects were seen even after microbes were filtered out, suggesting that microplastics and the cyclohexyl functional groups are responsible for the ailments in the fish.

The researchers also found unstable molecules called ROS (Reactive Oxygen Species) in the cells of the fish that developed abnormally. ROS build-up is known to damage DNA and affect animals in ways similar to what Abass and Nongthomba saw in fish treated with water from the slow-flowing and stagnant sites. Other studies have shown that microplastics and chemicals with the cyclohexyl group lead to decreased DO, which in turn triggers ROS accumulation in animals like fish.

A recent study from the Netherlands has shown that microplastics can enter the bloodstream of humans. So, what do the results from Nongthomba’s lab mean for the millions of people who use Cauvery water? “The concentrations we have reported may not be alarming yet for humans, but long-term effects can’t be ruled out,” he says. But he also admits that before they answer the question conclusively, they need to understand how exactly microplastics enter and affect the host. “This is something which we are trying to address now,” Nongthomba says.