Researchers at the Centre for Earth Sciences (CEaS), IISc have identified a way to estimate ancient seawater temperature by probing tiny bones in the ears of fish.

Oceans cover three quarters of the Earth’s surface and host many remarkable life forms. Earth scientists have been attempting to reconstruct the seawater temperature over time, but it is not easy to do so. “When you go back in time, you don’t have any fossilised seawater,” explains Ramananda Chakrabarti, Associate Professor at CEaS, and corresponding author of the study published in Chemical Geology. Therefore, he and his PhD student, Surajit Mondal, in collaboration with Prosenjit Ghosh, Professor at CEaS, turned to otoliths – tiny bones found in the inner ear of fish.

In the current study, they chose otoliths as scientists have discovered fossilised otoliths dating as far back as the Jurassic period (172 million years ago).

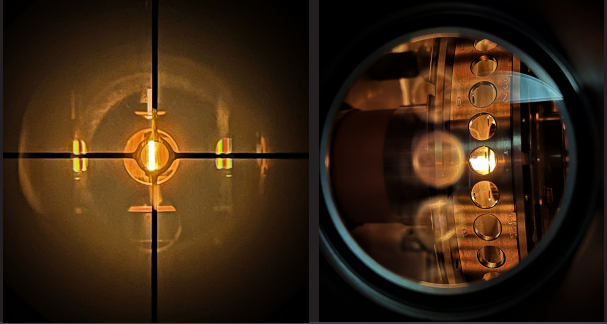

The researchers used six present-day otolith samples collected from different geographical locations along the east coast of North America. They analysed the ratio of different calcium isotopes in these otoliths with a Thermal Ionisation Mass Spectrometer (TIMS). By measuring the ratios of calcium isotopes in the sample, they were able to correlate it with the seawater temperatures from which the fish were collected. “We demonstrated that calcium isotopes are a powerful tracer of water temperature, and Surajit’s efforts make our lab the only lab in the country that can actually measure these isotopic variations,” says Chakrabarti.

In addition to calcium isotopes, the team also analysed the concentration of other elements like strontium, magnesium, and barium, and their ratios in the same sample, and collated the data together to tease out a more accurate value for seawater temperature within a range of plus or minus one degree Celsius when compared to the actual value.

Organisms that live in the ocean are extremely sensitive to temperatures. A two-degree temperature rise could lead to the extinction of several species. In addition, because the atmosphere and the ocean are “on talking terms”, says Chakrabarti, a lot of the carbon dioxide in the atmosphere eventually dissolves into the ocean, and this ability to dissolve carbon dioxide is also linked to seawater temperature – the lower the temperature, the more carbon dioxide is trapped. Just like a carbonated drink that loses its fizz as it warms up, the ocean loses its ability to hold carbon dioxide as it gets warmer.

Because of the close correlation they found between calcium isotope ratios and temperatures, the authors are confident that their approach can now be used on fossilised samples. Mapping early seawater temperatures is important to better understand Earth’s history, they say. “What happened back in time,” says Chakrabarti, “is key to our understanding of what will happen in the future.”