Ankur Chauhan’s lab tests how materials behave under extreme conditions

The evolution of human civilisation is often divided into epochs and eras based on significant political events, notable art, literature, and technological milestones. Yet one of the simplest ways to mark these transformative leaps is through materials – from the Stone Age to the Bronze and Iron Ages, and now to the Anthropocene, where human influence dominates the planet. Some refer to this as the Silicon Age, driven by powerful computers and AI; others prefer the Metamaterial Age or even an era of exotic, engineered matter.

If iron and steel fueled the Industrial Revolution, the fact that so many materials now define our technological moment speaks to their deep imprint on everyday life and the vast reach of modern science.

“Materials are the fabric of the universe, and in human terms, the foundation on which civilisations stand,” emphasises Ankur Chauhan, Assistant Professor in the Department of Materials Engineering at IISc. “Humanity once depended on just a handful of metals – iron, bronze, copper. Now we work with alloy systems refined over centuries, engineered from the atomic scale all the way to advanced manufacturing. With slight adjustments in composition or processing, it’s possible to reveal completely new behaviours. It’s a remarkable atomistic world we are trying to shape for a sustainable and advanced future,” he notes.

Everything around Ankur’s office suggests a certain order. Though scantily decorated, everything is exactly where it should be. His measured, thoughtful way of speaking often draws on metaphor – comparing the atomic disturbances caused when high-energy sub-atomic particles collide with materials in nuclear reactors to billiard balls scattering after a strike. Or linking the effect of stress fields resulting from differences in atom size and mass within alloys to the effect of space-time curvature around celestial bodies, shaped by their size and mass – to illustrate how mechanical properties emerge.

That clarity likely stems from the nature of his work, where understanding material responses with atomistic precision is essential. Ankur leads the Extreme Environments Materials Group (EEMG), which seeks to uncover how materials behave when pushed to their limits.

Growing up in Haridwar, Ankur was shaped by an environment that blended spiritual depth with an inherent scientific curiosity. His early fascination with engineering emerged from watching his father, an electrical engineer at BHEL, manage quality assurance for turbine generator sets destined for power plants. Those conversations planted the seeds for his curiosity about how things function and, more importantly, why they eventually fail.

Much of his childhood was spent exploring his curiosity about nature and the universe – reading, observing, and trying to understand how things worked. He wondered about how hydrogen fuses into heavier elements inside stars and how supernovae forge them. He says that the entire natural world, humans included, is essentially a “conscious collection of ancient stardust.” The iron flowing through our veins and the calcium strengthening our bones were cast in a star predating the Sun. This cosmic matter never disappears – it cycles endlessly: iron in the soil enters plants, becomes part of those who eat them, and returns to the Earth to reappear in another form.

Over time, this cosmic curiosity matured into a focused interest in understanding how materials evolve under different environmental conditions.

“It’s all part of nature … If we limit ourselves to Earth, certain materials may be considered natural here, but elsewhere in the universe or on other planets – where extremes of temperature and pressure exist – they may not even exist in the same form, or could appear in an entirely different state of matter,” Ankur explains. “In such contexts, materials science changes fundamentally, and pushes us to understand things from a different perspective.”

During his undergraduate studies in mechanical engineering, Ankur realised that the performance of many systems is fundamentally constrained by the materials themselves. Improving the efficiency of energy systems, for example, demands materials capable of withstanding extreme conditions, especially high temperatures. This insight led him to pursue a Master’s in metallurgy and materials engineering at IIT Roorkee. His journey then took him to the Max Planck Institute in Stuttgart, Germany, where he worked on nitriding – a surface treatment process in which nitrogen diffuses into metals to harden them, enabling their use in cutting tools and other wear-resistant applications.

The world of extreme conditions became central to his research during his PhD at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology in Germany, a major hub of nuclear materials research. “The group I joined there focused on the material requirements for next-generation nuclear reactors,” Ankur recalls. “Between 2014 and 2018, I worked on alloys being evaluated for Generation IV fission and fusion systems – reactors that operate at temperatures and irradiation levels far beyond current standards.”

Under such extreme conditions, materials must withstand intense heat loads, irradiation, and aggressive corrosion. Ankur focused on understanding the high-temperature behaviour of Oxide Dispersion Strengthened (ODS) steels. “Power plants experience significant load and temperature variations during shutdowns and startups, exposing components to creep, fatigue, and other degradation mechanisms,” he explains.

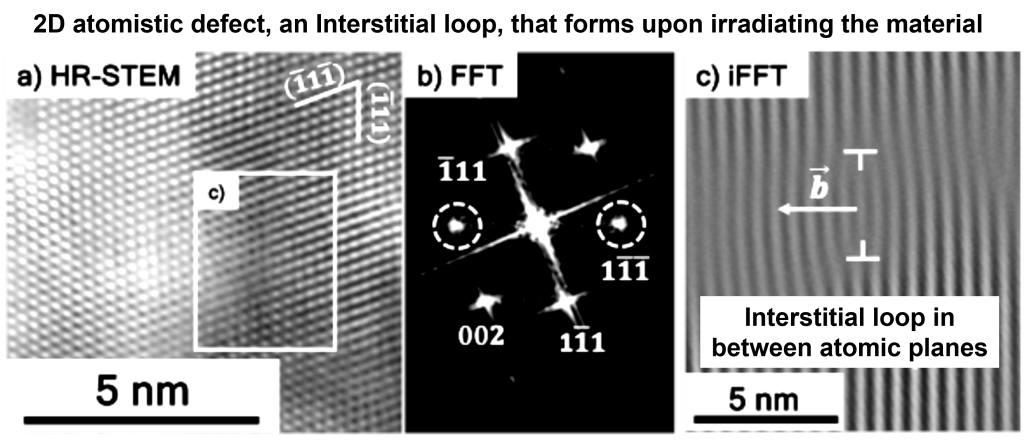

His work evaluated how reliably ODS steels perform under such simulated service conditions. He also developed new variants with tailored nanoscale oxide dispersions for high operating temperatures and employed advanced electron microscopy to uncover fundamental deformation and damage processes at play.

Electron microscopy, he explains, allows one to directly observe cause and effect – providing crucial feedback for designing improved materials. This tool became even more central during his postdoctoral work at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, USA, where he expanded his research beyond steels to investigate how ceramics respond to high-strain-rate loading. He worked on boron carbide ceramics for defense applications, including protective armour for soldiers and military vehicles, and also contributed to the development of advanced materials for MEMS (micro-electromechanical systems) in semiconductor technologies.

“To truly deepen your understanding of materials, you must broaden the domain you engage with,” he reflects.

Tuning material properties

After nearly two years in the US, he returned to Karlsruhe, Germany, to lead a research group investigating the effects of irradiation on candidate materials for nuclear reactors using in-situ electron microscopy, as well as the fatigue behaviour of high-entropy and multi-principal element alloys. Much of this work fed into the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) programme and other European Union and German collaborative initiatives. In 2021, driven by long-held aspirations to contribute to nation-building, he returned to India to establish his group at the IISc.

“At IISc, our group seeks to understand how materials perform across extreme environments – whether at very high or very low temperatures, under irradiation, shock loading, or high-strain-rate events. Our work has two core components: probing mechanical behaviour under such simulated harsh conditions and then characterising the resulting microstructures using advanced electron microscopy,” he explains. His team first identifies fundamental deformation and damage mechanisms, and then focus on improving materials by tuning compositions, introducing new phases or defects, or modifying microstructural length scales such as grain size.

Currently, a major focus of the group is developing strategies for designing fatigue-resistant alloys. By tuning the Cr/Ni ratio in the Cr–Mn–Fe–Co–Ni alloy family, or by engineering segregation-induced bands in high-strength steels, they have enhanced cyclic strength while retaining fatigue life – two attributes once thought to be mutually exclusive.

The group has also investigated the behaviour of novel alloys under high-temperature creep, high-strain-rate impact, shock loading, and irradiation, with direct application of these findings to organisations under India’s Department of Atomic Energy and Department of Space. These efforts aim to enable the deployment of damage-tolerant materials in extreme service conditions. In parallel, the group employs machine learning (ML) for property prediction, residual life assessment, irradiation effects, and the design of next-generation materials.

“We have projects with ISRO, DST, the Board of Research in Nuclear Sciences (BRNS), and others. We also have worked with companies like Boeing – studying how jet engine materials respond during takeoff, cruise, and landing, and developing ML tools to predict their remaining life,” he adds. Several national and international universities are part of these collaborations.

As an experimentalist, Ankur says he strives to make a meaningful impact on strategic sectors. At IISc, he has found an ecosystem where compelling research problems, enriching teaching opportunities, and world-class facilities come together. The experience is further shaped by the camaraderie of colleagues – whether over a cup of tea or coffee, during casual Friday frisbee games, or through spirited conversations.

“Much of our training focuses on helping students understand a problem, from atoms to components. Only when they can see the entire picture do they appreciate why a particular experiment is necessary,” he says.

He concludes with a reflection that loops back to his worldview: “Humans, like materials, have strengths and flaws. A few people learn to turn their flaws into strengths. How we adapt defines us – and materials behave no differently.”